A commentary regarding the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery written by Dr Martin Jaffa of Callander McDowell:

For clearer images of the graphs, please transfer to reLAKSation no 817 on our home page. Apologies for the technical hitch.

According to Dr Andy Walker, writing on behalf of Salmon & Trout Conservation, in 1988 the Loch Maree sea trout fishery collapsed. Even though Dr Walker maintains that the sea trout fishery collapsed, that year, anglers still managed to catch a total 1,081 sea trout from the Loch Ewe System which includes Loch Maree. Three years earlier, the catch had been 2,095 sea trout.

The anglers were mystified as to what could have brought about this collapse. The only thing that they could see that was different in 1988 that wasn’t there before was a salmon farm that had been established in Loch Ewe in 1987. They thus concluded that the introduction of salmon farming to the Loch Ewe System was ultimately responsible for the collapse of the sea trout fishery. For the subsequent thirty years, salmon farming has been the convenient scapegoat for the decline of rod and line fisheries, not just in Loch Maree and Loch Ewe, but along the whole of the Scottish west coast.

Salmon & Trout Conservation recently commissioned Dr Walker, a former Scottish Government fisheries scientist, to produce a report posing the question whether salmon farming was culpable for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery. Whilst Dr Walker expertly demonstrated that the fishery had collapsed, the evidence he offered that salmon farming was to blame was largely circumstantial. Dr Walker wrote that “a precise and quantifiable understanding of the impact of salmon farming has remained elusive.”

Salmon & Trout Conservation have used Dr Walker’s report to support their new campaign to remove the salmon farm from Loch Ewe with the intention that the Loch Maree sea trout fishery might recover to its former glory. However, relocating the salmon farm from Loch Ewe should be considered a retrograde step as it would be based on circumstantial evidence alone rather than hard facts. Salmon & Trout Conservation’s view seems to be that even circumstantial evidence means that there is a potential risk to wild fish which would be removed if the farm was relocated, but where is the line drawn. It could be argued that if the Loch Ewe farm poses a risk to the fish in Loch Maree, then every other farm poses a similar risk to wild fish and therefore should be relocated too, even though no evidence of a direct link exists.

In 2010, I was invited to debate the impacts of salmon farming on wild fish stocks with the then head of the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation, Malcolm Windsor, at Fishmongers Hall in London. The strong feelings expressed at this meeting piqued my interest in the relationship between salmon farming and wild fish and I have spent the ensuing years looking at why the passions I observed run so high.

The last two years have been spent re-evaluating the rod and line catch statistics collected by the Scottish Government to see how these relate to the presence of salmon farming. The results of this analysis do not appear to support Salmon & Trout Conservation’s campaign and I have been keen to hear their view. Over several months, I have made repeated attempts to speak face to face to Andrew Graham Stewart, Director of Salmon & Trout Conservation to discuss the findings but he has preferred to keep his distance. Instead, he has readily expressed his views in various articles and letters in both the angling and Scottish press. In a nutshell, he has not been very complimentary of the research. No doubt he thinks that the views of someone involved in salmon farming would reach a conclusion that is supportive of that industry. Of course, the same could be said of Mr Graham Stewart and his support of the angling sector.

The publication of Dr Walker’s report prompted me to look again at the catch statistics but this time using Mr Graham Stewart’s written comments to help guide the further investigation of the relationship between salmon farming and wild fish. For this help, I am indebted to Mr Graham Stewart.

In order that there can be no dispute as to the eventual conclusion of this search for answers, the ensuing journey can now be fully detailed. I believe I can now answer what happened to the Loch Maree sea trout fishery with three questions.

- Is salmon farming culpable for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery?

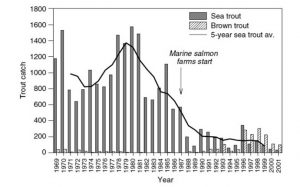

In 2006, Andy Walker published a paper with James Butler, former biologist with the Wester Ross Fishery Trust, detailing the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery. The paper included a graph of fish caught by anglers fishing from the waters around the Loch Maree Hotel. The authors helpfully highlighted the year that the salmon farms were established on Loch Ewe. This immediately raises an issue. Dr Walker states in his new report that the Loch Maree sea trout fishery collapsed in 1988. He also mentions that salmon farming came to Loch Ewe the year before. It is now widely established that salmon farms in the first year of their production cycle offer little risk to wild fish so given the time scale, it is difficult to comprehend how Dr Walker and Dr Butler can blame the Loch Ewe salmon farm for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery.

(from Sea Trout: Biology, Conservation and Management Edited by Graeme Harris, Nigel Milner 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd)

The publication of Dr Walker’s report prompted me to revisit this graph. I immediately wondered why that given the long history of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery and the Loch Maree Hotel (Queen Victoria stayed there in 1877), why does the graph only begin in 1969? It also struck me that the five-year average seems to suggest that the downturn occurred around 1979, eight years before the salmon farm was established in Loch Ewe. Finally, I wondered what had happened to the fishery after 2001?

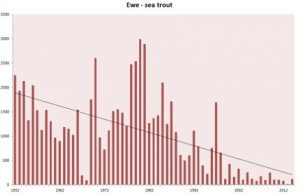

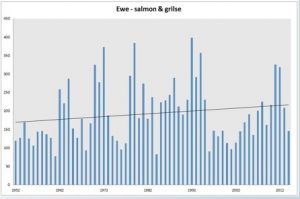

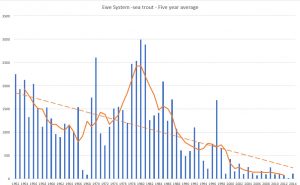

To answer this, I looked at the Association of Salmon Fisheries Boards (now Fisheries Management Scotland) Annual Review which includes graphs showing the most recent catch data. The graph for the Ewe System showed that sea trout catches have not improved as Salmon & Trout Conservation claim but what really caught my attention was the fact that the graph also showed rod catches of salmon. This was something of a revelation as throughout all the discussions about the collapse of fish stocks in Loch Maree, no-one had ever mentioned salmon. It was always all about sea trout.

The FMS Annual Review presents both the salmon and sea trout data on the same graph and because the size of the historic catches are so different it is difficult to see the underlying trends. I therefore asked Marine Scotland Science for the raw data so I could plot the graphs myself. The graph displaying sea trout catches begins in 1952, when the Government started to collect Scotland-wide data and shows the catch for the whole Ewe System and not just from the Loch Maree Hotel.

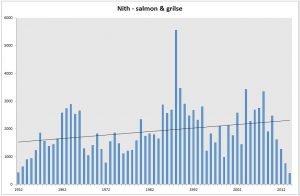

I applied Microsoft Excel trend lines to the graph and not unexpectedly, sea trout catches show the expect decline. Rather surprisingly, the graph of salmon catches shows a clear upward trend.

The obvious question arising from these two graphs is given that young fish swim out of Loch Maree into the short River Ewe and then out into Loch Ewe, possibly swimming past the salmon farm, where according to perceived wisdom, these young fish will pick up sea lice and then swim out into the open sea and presumably to their deaths, then why have sea trout catches declined and salmon catches increased?

I fortunately, I can turn to Mr Graham Stewart for a response. Writing in Trout & Salmon magazine, he says “if Ewe System salmon smolts (unlike salmon smolts from rivers at the head of long sea lochs, which may have to run a gauntlet past numerous farms) are able to migrate swiftly out through Loch Ewe at a time of low lice production on the Loch Ewe farm without attracting too many (or fatal levels) of lice, then they are comparatively safe and lice are unlikely to add to their marine mortality.”

However, it would seem that the Loch Ewe salmon farm must have had low lice levels at the time of the salmon migration for almost all of the last thirty years since salmon catches have not declined in the same way as those for sea trout. Mr Graham Stewart’s response doesn’t however explain why the salmon catch from the River Ewe has steadily increased over most of those years.

Meanwhile, Mr Graham Stewart continues “In contrast Ewe System sea-trout smolts remain in the immediate coastal area and thus are constantly vulnerable to infestation from lice emanating from local salmon farming activity; consequently, they are prone to attracting fatal levels of lice and their life chances (and growth) are severely compromised. The result is (or has been) the collapse in the Ewe System’s (including Loch Maree) mature or large sea-trout population.”

This statement appears a little confusing because Mr Graham Stewart seemed to be saying that only the largest sea trout have disappeared from Loch Maree not all the fish. However, if the whole stock had collapsed, inevitably the largest fish will have disappeared too.

Mr Graham Stewart implies that sea trout, unlike salmon remain in the vicinity of the home river and thus could pass back and forth near the farm, picking up more lice every time they do. Mr Graham Stewart appears to have a valid argument however, another observation obtained from the fish catch data confuses this view.

When I obtained the raw catch data from Marine Scotland Science for Loch Ewe, I also requested the data for all of the 109 fishery districts in Scotland. Similar patterns of opposing catch trends, with one increasing whilst the other declines, were apparent in more than one other fishery district.

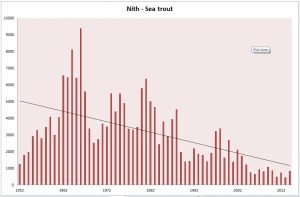

One set of data was especially of interest and this was for the River Nith. The catch trend graphs for the Nith look remarkedly similar as those from the Ewe System.

What makes the River Nith of interest is that it emerges into the Solway Firth not far from the English border, some 130 km from the nearest salmon farm. River Nith sea trout smolts may well linger in the vicinity of the river mouth but they do not come into contact with sea lice from a salmon farm simply because they are too far away. Is it possible, that whatever is causing the River Nith sea trout catch to decline, and clearly, that cannot be salmon farming, is causing a similar decline in the Ewe System?

Mr Graham Stewart has an answer. He writes “Dr Jaffa refers to one river in particular- the Nith. He asks ‘why are River Nith sea trout catches are in decline when they are more than a hundred miles from the nearest salmon farm?’ This is a complete red herring. The Nith, in common with the rest of the non-salmon-farming areas of Scotland, has not lost all of its mature sea trout – as the (2016) river reports in Trout & Salmon magazine confirm with references such as ‘six sea trout to 3lb’, ‘5lb sea trout’ and ‘two sea trout with a combined weight of 11lb 8oz’.”

Mr Graham Stewart might be proud to highlight such notable catches but actually according to the 2017 Fisheries Management Scotland Annual Review, the heaviest sea trout caught from the Nith in 2016 weighed in at an impressive 10lb.

Mr Graham Stewart says that the Nith is a red herring but in fact catching a fish of 10lbs in the Ewe System was always a rarity. The great fisheries writer, Augustus Grimble, indicated in his book of 1904 that larger sea trout caught from the Ewe were typically around 5lb in weight. This was long before any salmon farms were established in Loch Ewe.

Andrew Graham Stewart then continues “Furthermore, the Nith hardly bears comparison to the Ewe System; the former meanders through coal mining and agricultural land whereas the latter runs off barren mountainous terrain.”

This is a very puzzling statement for Mr Graham Stewart to make because a year ago, Salmon & Trout Conservation issued a press release comparing catches from east coast rivers with those from the west coast. They stated: “The only significant difference between the two coasts is the presence of aquaculture on the West.” Catches made from the east coast had increased whilst those on the west coast had declined when expressed as percentage growth compared to the catches from 1970. S&TC argued that the only difference between the coasts was the presence of aquaculture. This is despite major differences in the nature of different river systems which also clearly impacts on catches. For example, the east coast River Tay is 120 miles long whilst the River Ewe is just two miles in length. They are very different rivers and the numbers of fish caught will reflect this.

Although the River Nith is located in the south west, it is just as dissimilar to the Ewe as the Tay. If the Tay can be compared with the Ewe, then so can the Nith, despite Mr Graham Stewart’s claims otherwise.

One final comment concerning the Nith is that whilst Mr Graham Stewart argues that using this river as a comparison is a red herring, he fails to make any attempt to explain why sea trout catches from the river have declined. If it is not salmon farming that is to blame then clearly some other factor is responsible for the decline.

Instead, Mr Graham Stewart deflects attention away from the River Nith saying that “a far more relevant comparison is the Hope System on the north coast, which flows through similarly mountainous terrain.” However, he is incorrect because the comparison of the River Ewe and the River Nith compares one river that has salmon farming activity with one that doesn’t. Unlike the Nith, the Hope System is home to two salmon farms, something that Mr Graham Stewart does acknowledge. He writes that “there are two small salmon farms – the only farms on this coast – in Loch Eriboll to the south-west of the south of the Hope.” Mr Graham Stewart, also points out that according to the industry’s sea lice data, these two farms have been essentially free of lice for almost two years (2015 & 2016).

It is not clear which figures Mr Graham Stewart consulted, but the SSPO data shows that the farms in Loch Eriboll did suffer a significant sea lice attack in early 2015 after which they were laid fallow for well over a year. Yet, whether the farms were sea-liced or not appears irrelevant to Mr Graham Stewart because his view is that “as long as the Hope’s sea trout do not enter Loch Erriboll, they will not even pass the cages, rather if they go north from the mouth of the river they are into the edge of the open Atlantic with strong parasite-dispersing current. Here they are able to survive and mature and indeed thrive.”

What is unclear is whether these sea trout head straight out to sea or not. However, when he discussed the behaviour of sea trout in Loch Ewe, he indicated that the young sea trout do not head straight out to sea but rather linger in the sea loch. Why would they not do the same in Loch Eriboll as they do in Loch Ewe? The mouth of the River Hope may be high up the loch, but the fish are still free to hunt for food within the confines of the loch rather than risk the strong currents along the north coast.

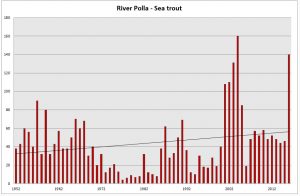

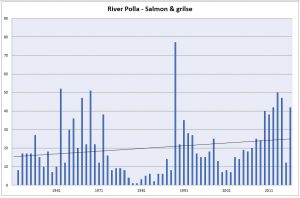

What Mr Graham Stewart fails to mention when drawing attention to Loch Eriboll is that the River Hope is not the only river to empty into the loch. The River Polla is not a well-known river and doesn’t even feature on the Salmon Atlas ranking of top Scottish salmon rivers. It is however included in the Fisheries Management Scotland Annual Review. In 2016, this short river with only two miles accessible to fishing produced a total catch of 140 sea trout. This was the second most prolific year since records began in 1952 and clearly exceeds the ten-year average sea trout catch of 45 fish. The heaviest fish landed in 2016 weighed in at 10lb, the same weights as the heaviest fish caught from the River Nith.

The River Polla’s impressive catch should be widely lauded by the wild fish sector but Salmon & Trout Conservation have, for one, remained strangely silent. This is not unexpected because the evidence from River Polla does not support Salmon & Trout Conservation’s campaign to vilify salmon farming and to call for the relocation of the farm from Loch Ewe.

The River Polla and the Ewe System actually have much more in common than they do that is different. The Ewe and the Polla are short rivers, each with two miles of accessible fishing. Both rivers empty into the head of their respective sea lochs, each around 16 km long and any smolts that enter the loch then have to swim past a salmon farm in order to reach the sea. According to Mr Graham Stewart, in swimming past the farm, these smolts will risk death from sea lice. However, in the case of the River Polla, this does not seem to have happened.

The obvious question is why are catches so different in these very similar rivers systems? If the sea trout fishery in the Ewe System has collapsed because of salmon farming, then why has the River Polla this year produced almost record catches?

Maybe Mr Graham Stewart will come up with some explanation, like a rabbit out of the hat, in order to explain the differences between the Ewe System and the river Polla but as he is unwilling to meet to discuss such issues face to face, then I will have to wait until he provides his account in a forthcoming issue of one of the angling magazines in which he writes. Meanwhile, the only conclusion that might be drawn is that perhaps salmon farming is not the primary cause of the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery as Mr Andrew Graham Stewart and Salmon & Trout Conservation suggest.

- If salmon farming is not too blame for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery, then is there another feasible explanation?

In his report, as commissioned by Salmon & Trout Conservation, Dr Andy Walker wrote: “Visiting anglers used to come (to Loch Maree) with realistic expectations of large feisty specimen fish caught in a wonderfully scenic and tantalisingly remote, atmospheric and mountainous environment, epitomising the West Highlands of Scotland. Instead the catches of sea trout plummeted after 1987 and the specimen fish which characterised these famous waters were gone.”

The disappearance of large fish is very reminiscent of another fishery; that of North Sea cod. The Daily Telegraph famously reported at the time that there were estimated to be fewer than 100 adult cod left in the North Sea. The newspaper blamed overfishing. Could the same fate have befallen the Loch Maree sea trout fishery?

Dr Walker’s graph illustrating the collapse of catches in Loch Maree, taken from his 2006 paper includes data representing the five-year catch average. I have also calculated a five-year catch average stretching back to 1952. This rolling average highlights that catches from the time series of 1969 onwards, on which Dr Walker has focused, appear to be unusually high for the Loch Ewe System. In fact, the period prior to the collapse of the sea trout fishery in 1988 is about the only time that catches exceed the trend line for the Loch Ewe fishery.

One possible reason why sea trout catches boomed for four years from 1979 is that there may have been more fish returning to the loch due to improved superintendence around Loch Ewe. This had been introduced to combat illegal fishing in the loch and may have allowed more fish to become accessible to anglers.

Another reason may be due to the nature of the fishery operated by the Loch Maree Hotel. Dr Walker used catch data from the Loch Maree Hotel rather than from the Scottish Government in both his 2006 paper with James Butler and in his report for Salmon & Trout Conservation. This choice was because the hotel fishery was based on two rods in each of nine boats fishing very day of the season, year in and year out. This meant that the catch equated to a similar fishing effort each year. However, whilst the impression is given that the fishing effort was constant, it might not have been. This is because the ghillies who attended each boat were of varying experience. The hotel relied on a couple of local experienced ghillies but then often supplemented them with others who were not as knowledgeable of the loch, including sometimes students looking for summer work. It is possible that the ghillies used from 1979 on were much more experienced and ensured their clients always caught fish, whereas at other times, the knowledge and experience may have been lacking. I have spoken with someone who whilst a student worked as a ghillie on Loch Maree in 1984 and who related his own experiences of his time there.

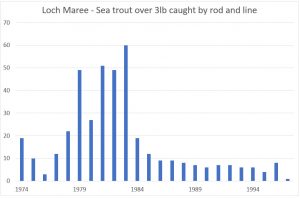

The improved fishing from 1979 onwards meant that not only were anglers catching more fish, they were catching more larger fish.

From the beginning of the 1980’s the catch of the largest fish increased nearly threefold. Catching and killing these fish removed the most fecund adults from the Ewe System and may have contributed to the subsequent collapse of the fishery later that decade.

Anglers may have overfished the loch but the UK Government also contributed to the subsequent decline in catches. In 1984, the new Inshore Fisheries (Scotland) Act removed the three-mile limit for fishing boats and these soon entered Loch Ewe in search of herring and mackerel. Within a short period of time, stocks of these fish in Loch Ewe were wiped out and undoubtedly so too were any sea trout that had remained in the loch.

In his report, Dr Walker stated: “Over-exploitation of the sea trout stocks did not seem a plausible explanation for the abruptness of the changes in stock composition and collapse of catches that occurred at the end of the 1980s”.

However, given the fishing increased pressure from both fishing boats and anglers in the Ewe System, it is not surprising that the fishery did actually collapse.

- Why has the Loch Maree sea trout fishery not recovered?

On the home page of their website, Salmon & Trout Conservation state: “Fish farming is destroying West Highland and Hebridean wild salmon and sea trout stocks and iconic sea trout fisheries like Loch Maree are no more.”

Since 1988, which is when Dr Walker says that the Loch Maree sea trout fishery collapsed, anglers have managed to catch and kill a total of 6,016 sea trout from the loch; a loch whose fishery is ’no more’.

For a fishery that has collapsed, 6,016 sea trout is a significant number of fish. However, this sustained removal of sea trout from the loch also represents a continued loss of breeding stock which has prevented any chance of long-term recovery. According to the official catch data, the last fish to be caught and killed from Loch Maree was in September 2016 when 5 young sea trout (finnock) were taken. The average weight of these fish was just ten and a half ounces or 300g. This is about the size of a whole rainbow trout sold from a supermarket fish counter. It’s no wonder that fish are not breeding when they are killed at such a small size

There is one final point and that is sea trout are simply the migratory form of the freshwater brown trout. It is thought that when food is limiting, the trout produce the migratory form which can swim out to sea to access more available food sources. In recent years, warmer temperatures have boosted the food availability in freshwater favouring the freshwater form of the trout. Accounts suggest that many fisheries on the west coast are now awash with brown trout. This will reduce the likelihood of any recovery of sea trout across the whole of the west coast, not just Loch Maree.

Salmon farming provides a ready-made scapegoat for Salmon & Trout Conservation. Sea lice are a problem for salmon farmers and undoubtedly some wild fish do pick up sea lice from salmon farms but fish like salmon and seatrout produce hundreds of eggs in the expectation that many will not survive. Weak and sick fish are an easy target for lice but it is likely if these fish didn’t pick up lice, they would die from some other cause anyway.

The River Polla and Loch Hope show that salmon farming and wild fisheries can co-exist together in harmony. Unfortunately, the wild fish sector, including Salmon & Trout Conservation, look to blame anyone else for declining stocks but themselves.

Finally, one aspect of the decline of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery that hasn’t been discussed is the wider decline of sea trout not just along the west coast of Scotland but throughout Scotland as a whole. Sea trout numbers in England, Wales and parts of Europe have also declined too so the problems on the west coast are not unique.

A comparison of sea trout catches from east coast and west coast fisheries from 1970 in fact shows that the decline in catches along both coasts is very similar despite a big difference in the number of fish caught.

The similarity of the trend lines would suggest that the decline on both coasts is perhaps the result of the same influence. This means that salmon farming cannot be to blame since there are no salmon farms along the east coast.

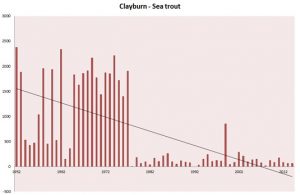

There is one last observation and this relates to the fishery district of Clayburn in the Outer Hebrides. The catch data shows that sea trout catches collapsed in 1978 and within one year unlike the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery. The cause of the collapse is unknown but it occurred four years before any farm was established in the locality. The fisheries sector appears to have made no attempt to determine any other cause of the collapse, nor was the collapse publicised, unlike the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery.