Great news: The Carron, the river that empties into one of the largest aquaculture hubs on Scotland’s west coast, has published its report for the 2019 season. This states:

‘While the previous season was a good one, 2019 was even better, with the catch of salmon and grilse well above the 10-year average. Some excellent salmon were caught, with several in the 20lb class, and the grilse run was particularly strong. Winter spates and moving gravel are still problematic, but a highly successful stocking programme using well established fry, which has been operating since 2001, has mitigated this and other problems. Smolt output is well above what might be expected and has resulted in recent catches being at historically high levels. The current 10-year averages for salmon and grilse are 98.4 and 147.9 respectively, compared with 16.8 and 6.5 for the 10-year period immediately prior to the stocking programme kicking in.’

This is really great news especially given that Richard Sankey, Chairman of Fisheries Management Scotland has written catch ‘figures for 2019 taken together with those of recent years, confirm this iconic species is now approaching crisis point’.

Mr Sankey’s statement and the River Carron river report both appear in the 2020 Fisheries Management Scotland Annual Review, which is available to download from the FMS website. This review was published without any publicity which might suggest a reluctance to share this report. This isn’t of any surprise because of the contradictory messages contained within. Salmon is in crisis but on the River Carron, catches are higher than ever.

Mr Sankey continues in his introduction to the review (page 3) that ‘The threats to our iconic fish species are complex and multifactorial and there is no single reason for the declines. However, it is important to emphasise how few of these pressures are under the direct control of fisheries managers.’

On page 4, in a section titled ‘Fisheries Management Scotland in 2019’, the three members of staff write that ‘It is important to emphasise that the vast majority of pressures which our fish face are not under the direct control of fisheries managers.’

Both Mr Sankey and the FMS staff go on to stress how important it is that FMS work collaboratively with Scottish Government and agencies to prioritise and ultimately address these pressures, given that they are outside the control of fisheries managers.

Simply put, what Mr Sankey and FMS appear to be saying is that if wild salmon is in crisis then it has nothing to do with the wild fish sector. It is only necessary to look elsewhere in the review to see where FMS consider the problems lie, with pages 12 and 13 devoted to finfish farming but more about that later.

What is of most interest is that the review includes reports from some of the most important salmon rivers in Scotland with details of their catches of wild fish during 2019. In the past, these reports have provided an indication as to the state of salmon stocks before Marine Scotland publish the official data. This year, I was particularly keen to see these reports given that after 68 years, Marine Scotland will no longer be publishing catch data for the Ewe System and Loch Maree. Due to the importance ascribed to Loch Ewe catches of salmon and sea trout by some sections of the wild fish sector, this is a major omission, if not a national scandal.

Unfortunately, FMS have followed Marine Scotland’s example and this year have failed to include the Ewe in their river reports. The only other district missing from the review is the River Forth, on Scotland’s east coast and after making some enquiries, it seems the River Forth has not been included because the reported catches were considered too unreliable. This raises all sorts of questions about how data is recorded and supplied and Its only necessary to look at the entry for the River Forth that appeared in the 2019 Annual Review to have concerns.

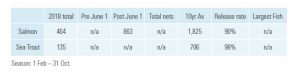

This shows that 464 salmon were caught in 2018, yet the number caught after the end of the spring regulations from June 1st indicates that 863 fish were caught! By comparison, the Marine Scotland data records that a total of 729 wild salmon and sea trout were caught in 2018, of which 64 were killed and kept.

Meanwhile, I have been unable to ascertain why the report for the Ewe System has not been included but of all rivers usually listed, its absence is the most telling.

Even with two reports missing, it is still possible to gain an insight into the state of salmon stocks in Scotland in 2019. In total, the review contains 45 river/district reports out of the 109 that are listed by Marine Scotland. In 2018, the Marine Scotland data recorded a total rod catch of 37,916 of which 2,475 were caught and killed. By comparison, the 47 river reports that were published by FMS in their Annual Review recorded a total catch of 34,197 wild salmon and grilse, which equated to 90% of the Marine Scotland total.

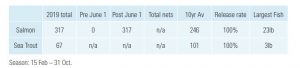

This year, the FMS data for 45 rivers/districts totals 40.606 wild salmon: an increase of 6,409 fish over that of 2018. In an introduction to the reports, FMS write in their review that catches have marginally improved in 2019 compared to 2018, which were the lowest on record. They say that this is in part due to improved fishing conditions as many rivers suffered from a drought in 2018,

Whilst anglers manage to kill 2.475 wild salmon and grilse for sport last year, an estimate (and I stress that this is just an estimate as it is based on the stated percentage released and therefore subject to error) of the fish killed in 2019 is 3,272 salmon and grilse. It is therefore not surprising that FMS continue their introduction to the river reports stating that ‘Atlantic salmon stocks are presently facing considerable pressure due to a range of factors. Despite this, Scotland remains capable of supporting good angling opportunities throughout the year.’ Why these angling opportunities must include even killing one fish is unclear.

As previously mentioned, both the Chairman and the staff of FMS clearly say that the vast majority of pressures facing wild salmon are not under the direct control of fishery managers. Surely the killing of wild salmon is very much under their control and could be easily stopped. If wild salmon are in crisis and considered to be a national priority, then why is the killing of fish for sport still allowed?

Returning to the river/district reports, 7 out of the 45 are located in the west coast Aquaculture Zone. In total they produced a catch of 1,406 salmon and grilse or less than 4% of the total FMS report catch. Of course, the wild fish sector will say that this figure is so low because the salmon farming industry has wiped out stocks of wild fish. Yet, the 2019 catch shows an increase on that of 2018. Excluding the Ewe system, the total salmon catch out of these seven fisheries in 2018 was 1,209 fish, an increase of 16%, whereas the total increase for all FMS reports from 2018 to 2019 was around 18%. It would seem that west coast fisheries are not that much out of sync with their east coast counterparts despite being of such a different nature. If salmon farming is so damaging to wild stocks, why are anglers still managing to catch so many fish. After forty years, surely all stocks would have disappeared long ago, especially as production has increased so much.

As I mentioned earlier, the Annual Review includes two pages devoted to finfish farming. Most of this is a review of projects such as the proposed west coast tracking project which they hope will provide vital information. I’m all in favour of vital information and it would be great if I could access such vital information from the wild fish sector, especially as it has been available for the last 68 years. Unfortunately, data about wild fish in Scotland is increasingly hard to come by. Whilst FMS, as well as others in the wild fish sector, want vital information from salmon farms, they are increasingly less keen to provide even the basic information about their own activities.

The section in the review about aquaculture points out that the Government and the Industry must move quickly to achieve a position where Scotland can be compliant with international commitments to NASCO. Apparently, this should include no increase in lice-induced mortality of wild salmonids. Unfortunately, I have not seen any evidence by which this can be judged. It is all circumstantial. The aquaculture pages of the report include a photo of sweep netting for sea trout to monitor sea lice. This method does not provide any evidence that wild salmon stocks are impacted by sea lice from salmon farms. Yet, smolt release studies show that if there is any impact it is only about 1-2%. I am unclear why FMS don’t seem to take such evidence into account other than it undermines their long-held belief that salmon farms are the underlying reason why wild fish stocks are in decline.

Of course, FMS now have to be a little more circumspect about their views on salmon farming. This is because they have to be seen to be co-operating with the salmon industry rather than overly criticising them to keep the Scottish Government happy. In exactly the same way, the SSPO are soon to make a significant financial donation to FMS as a way of being seen to be cooperating with the wild fish sector. Unfortunately, there is a big difference between FMS being seen to be cooperating and SSPO funding FMS, and that is that there is little commitment from FMS in return. I don’t suppose that they will impose an immediate ban on the killing of wild fish for sport as a way of safeguarding stocks for the future. I suspect that the killing of wild fish for sport will undoubtedly continue. Surely, there can be cooperation between the farming and wild sectors that doesn’t involve salmon farmers giving money to those with heritable fishing titles.

Unlike previous Annual Reviews, FMS have included a page in which they provide a list of their achievements in 2019. This is a summary of their member contribution to protecting and improving their fisheries and freshwater habitats. This is really a measure of what FMS have done to protect wild stocks for the future.

- 25 barriers eased or removed to which members have contributed time or money

- 163 km of river newly accessed following barrier removal

- 77 offences formally reported to Police Scotland

- 71 illegal instruments retrieved/confiscated

- 562km of rivers managed for invasive species

- 223 pollution incidents reported to SEPA

- 263 schools worked with – 14,075 pupils engaged

- 48,400 native trees planted

..and they say wild salmon are in crisis! Hopefully, if the SSPO are determined to fund river proprietors and their heritable fishing rights, then the money will be put to better use to safeguard wild salmon than by the actions indicated above.

Finally, I would return to the report from the River Carron. This is a great success story with larger than ever catches within the heart of the Aquaculture Zone. This is something that should be championed and publicised. Yet, this success story is buried in page 33 of the review and it fails to merit even a mention from the Chairman or the staff of FMS elsewhere in the review. The SSPO should read the Carron river report carefully and think again that if they want to support wild fisheries in Scotland and especially the west coast, then funding should go direct to enlightened local river managers like those on the Carron who have shown that they can actually safeguard the future of wild salmon rather than those who think that the successful protection of wild salmon means catching poachers and reporting pollution, and not forgetting overseeing the killing of an estimated 3272 wild fish for sport.

Jethro Tull: One side effect of the Coronavirus is that the keyboard warriors have a lot of time on their hands and have ramped up their criticism of the salmon farming industry. One retweet that caught my attention said ‘The industry needs banning. I thought it was a bad idea when I first heard Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull was getting into it in the 80’s’. For those who may not be old enough to remember, Jethro Tull was a rock group formed back in 1967.

By total coincidence, one of my regular correspondents sent me a link to an amalgam of videos about Ian Anderson’s purchase of the Strathaird Estate on the Isle of Skye and his interest in farming salmon. It is on You Tube and can be found by searching for ‘Ian Anderson – The Laird of Strathaird’ or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eIB97LiNFjk

What is interesting about this video is Ian’s comments about wild salmon. In an interview from 1983, Ian says salmon farming ‘really does take the pressure off the wild species and I think most people are aware that wild salmon are diminishing in numbers or at least are being caught in less numbers. They have certainly been over-fished for a great many years now and the last two or three years we have certainly seen a decline in catches and an increase effectively in the price which has ironically made it possible to farm salmon in the first place. If the wild were more plentiful the price would be lower – simple supply and demand – and it would not be economic to farm the species.’

At the time of recording, the industry, as a whole, was producing about a thousand tonnes of farmed salmon. This is not even the total production of one modern day farm. It is inconceivable that such a small industry could be responsible for the declines of wild salmon mentioned by Ian Anderson. The reality was that wild salmon stocks were in decline long before salmon farming arrived on the west coast. Sadly, the wild fish lobby prefer to ignore this reality and blame salmon farming for declining stocks.

Finally: A couple of unrelated stories published by the Guardian newspaper caught my attention this week. The first relates to concerns about changing weather at this time of year with sudden cold snaps that might lead to a rise in infections of Nematodirus or thread-necked worms in new lambs after they are put out to pasture. Infections of these worms are usually mild, but lambs can ingest large numbers of the worms under certain circumstances and can suffer severely. The Guardian highlights that up to 30% of new lambs can die from such infections.

I mention this because critics of the salmon industry repeatedly state that terrestrial farming never suffers from high mortality. This is yet another example that shows salmon farming is no different from any form of agriculture and under certain circumstances can experience infrequent examples where mortality is higher than would be expected.

The second story concerns evolutionary changes to the nightingale, a migratory bird feted by the poet John Keats and much celebrated for its beautiful song. Researchers in Spain have found that the birds might have become increasingly endangered because their wings are now shorter than they used to be. It appears that wing size is linked to larger numbers of eggs and a shorter lifespan. Selective pressure from climate change on one of these traits will therefore affect the others. The scientists have found that the pressure of drought has led to the most successful birds laying fewer eggs and thus fewer young to feed. However, because of the linked traits, fewer eggs mean that the birds are also developing smaller wings and thus less able to endure the long migration. The scientists have found that climate change is having an impact on migratory birds with changes to arrival and laying dates and the physical features.

The obvious question is whether the decline in wild salmon is the consequence of such climate induced evolutionary changes too. I am reminded that one of the first issues I considered in my research about wild salmon was whether genetic drift had had a role to play in the changing nature of wild salmon stocks. Over the last couple of hundred years, the numbers of wild salmon caught by both nets and rods may have significantly reduced the salmon population gene pool leading to the occurrence of genetic drift. It is worth remembering that when marine fish stocks are over-exploited, a cross selection of the population is removed but with migratory fish such as salmon, it is only ready-to-breed adults that are removed along with much of their genetic variety. Such a loss could well impact the ability of the fish to adapt to changing conditions.

I suspect that the wild fish sector are too busy blaming salmon farming to consider such implications.