A National Priority

This week, the press and media were awash with reports that the wild salmon sector have called for ‘salmon conservation’ to be treated as a national priority. This call has been reported differently by different papers, so I was pleased to be sent a copy of the original Press Association release. According to Dr Alan Wells, Chief Executive of Fisheries Management Scotland, official catch figures for recent years confirm this iconic species is now approaching crisis point. He said whilst some of the factors impacting on wild salmon may be beyond human control, Scotland’s Government now have a historic opportunity to do everything in their power to safeguard the species in those area where they can make a difference. This is because nature is sending us some urgent signals.

Perhaps the main signal that salmon are sending to Dr Wells is for anglers to stop chasing, harassing, molesting and killing wild salmon for sport. If wild salmon stocks are so threatened, then surely the most obvious solution where they can make a difference is to stop all fishing for the species, especially given that salmon are typically targeted when they are on the way to their home river to breed and secure the next generation. Since 1952, when the Scottish Authorities began to record salmon catches, over 5.9 million wild fish have been caught and killed for sport. Is it not surprising that there are fewer than ever fish remaining?

Of course, the Scottish Government are unlikely to ban angling because of the power of the angling lobby. However, it does seem that the wild fish sector cannot be on one hand demanding increased conservation of stocks simply to provide more fish for them to catch for sport. To reinforce the point, the Press Association release includes a comment from Karen Ramoo, policy adviser at Scottish Land and Estates who said that Scotland has world renowned fishing, which significantly contributes environmentally, socially and economically and that the environment and rural economy are at risk if we do not act now to tackle declining salmon numbers. Sadly, Ms Ramoo is wrong. Scotland had world renowned fishing. Anglers may still come to Scotland based on the past image but if they fail to catch fish, they will not return, and the fisheries they visit will collapse regardless.

The Press Association release mentioned that representatives of the wild fish sector were to meet politicians at the Scottish Parliament to discuss what could be done to reverse the trend. As yet it is unclear whether any solutions as to how to safeguard the future of Scottish wild salmon were proposed. However, I suspect that nothing new was considered because the event was led by the same angling people talking about the same angling related issues that have been repeated many times over.

One of the main speakers at the meeting was the Environment Secretary Roseanna Cunningham who said that the Scottish Government will do everything possible to safeguard the future of Scotland’s wild salmon. She then announced £750,000 of funding for an innovative project between the Scottish Government, the Atlantic Salmon Trust and Fisheries Management Scotland to work together to track salmon smolt migration on the west coast of Scotland and thereby seek to improve the understanding of this important fish.

However, if Ms Cunningham is under the impression that providing £750,000 of funding is even going in part help safeguard the future of wild salmon, then inevitably she is going to be sadly disillusioned. This project is going to do little to help secure Scotland’s wild salmon stocks and this is simply because for as long as records have been kept, 90% of the Scottish salmon catch is taken from east coast rivers. The west has contributed less than 10% of the fish caught. Even if west coast stocks could be returned to peak levels, it will make little difference to the overall catch. The real problems for wild salmon are on the main rivers of the east coast.

According to many within the wild fish sector, salmon runs in west coast river have already been destroyed by salmon farming with many stocks already facing extinction. Because salmon farming is always cited as the being the cause of the west coast collapse, almost no consideration has been given to other possible causes. For example, the number of returning fish has fallen down to below 5% from at least 25% in the early 1980s. The effect of this decline would be noticeable much earlier in the west where rivers are short and spate. By comparison, the east coast has had a large reservoir of fish in the major rivers and these have buffered east coast stocks against the inevitable effects of fewer returning fish that is until recently.

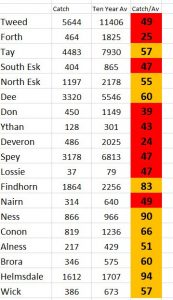

The decline of catches can be seen in the following table which lists the 2018 catch and the ten-year average for most east coast rivers. This data is taken from Fisheries Management Scotland’s Annual Review 2019 (http://fms.scot/publications/fisheries-management-scotland-annual-review-2019/). The 2018 catch is also expressed as a percentage of the ten-year average. Those highlighted in red are rivers where the percentage is less than 50% whilst amber shows rivers from 50-100%. Any river where the catch is above the ten-year average would be shown in green. The data for 2019 will not be available until March if not April.

The situation for east coast rivers does not look so good. It was not always so. The River Don which in 2018 had a catch percentage of the ten-year average of 39% was 127%. The Tweed which is currently 49% was 113%.

By comparison, the same data format for the west coast is rather surprising with two of the rivers showing catches above their ten-year average.

As yet, the data for 2019 is not available but I have acquired that for the River Carron and whist Dr Wells suggests that salmon stocks are in crisis, the catches from the Carron have improved. The 2019 catch was:

![]()

The Environment Secretary told the Parliament meeting that the change in numbers of salmon returning to Scottish rivers is of great concern and caused by a range of complex factors. It is certainly the case that the pressures on individual stocks are probably unique for every river because of the differences in geography, geology, rainfall, water flows and so on. However, if the aim is to safeguard stocks of salmon for the years to come then surely it makes more sense to understand what is happening in those rivers where catches are currently increasing rather than spend huge sums on some tracking project that will do little to help declining east coast stocks.

Catches vary from year to year and the previous years catches from the Awe were only about 35% of the ten-year average resulting in a massive swing from year to year. However, the River Carron has shown increasing catches for the previous four years, whilst most rivers on the east coast have been in decline.

What makes the River Carron so special is that the river empties into the biggest Aquaculture hub on the west coast. If wild salmon are going to suffer from the impacts of aquaculture in any river then it surely must be the Carron, Yet, the fishing has been really good and so has the number of fish landed. There are other factors that might affect the Carron, but I will explore these in a forthcoming issue of reLAKSation.

Rather than examine the reasons why some rivers are bucking the trend, the Atlantic Salmon Trust and Fisheries Management Scotland have partnered with the Scottish Government to attempt to plot the migration routes of salmon smolts as they leave west coast rivers. I am not sure why this will help safeguard wild salmon unless the intention is to link migration routes with the location of salmon farms. The wild salmon sector has for long blamed the decline of wild salmon stocks on the transfer of sea lice from salmon farms to migrating smolts. All the evidence is circumstantial but even if this project does show that some smolts pass near a farm, it still does not provide a link between salmon farms and declining stocks.

Regular readers of reLAKSation will remember that Marine Scotland Science conducted a three-year £600,000 project to try to link the number of returning salmon to sea lice infestation, but their project failed comprehensively to demonstrate any connection. One reason was that the experimental design was inherently flawed, and the project should never have left the drawing board. I can see similar parallels in the current plans. I suspect that the Scottish Government would be better served giving the £750,000 to homeless charities rather than invest it in this project. It will certainly do much more good that way.

I have previously highlighted concerns with the ongoing east coast tracking project in that the AST announce that 60% of migrating salmon smolts died on their way down the selected rivers. In fact, the AST can’t be sure that these fish died at all. What they do know is that the passage of the fish was not recorded. This might be because the fish died but equally it could be because the tags weren’t detected by the arrays. The tags may have failed or so may have the arrays or the conditions meant that the arrays simply failed to pick up the signal from the tag. There is also a risk that the tags might have killed the fish.

It is clear from the communications from the FOI request that such concerns still exist. For example, there is the possibility that the arrays may be strung in close parallel so that if one fails to pick up a fish, then the second might. It is proposed that the arrays are strung between the Lewis and the Mainland (42.7km) and South Uist and Skye (25.5km) with other arrays to fill in the gaps. This simply means that fish will be detected if they swim up the Minch. There is a paper by Marine Scotland that suggests that sea lice from a salmon farm can infect smolts up to 31km away so it could be argued that the arrays will be in range of at least one salmon farm. Although the paper’s assumptions were incorrect, I can see that any result will be given as case proven.

For many years, the wild fish sector has argued that salmon farm locations should be approved using a precautionary principle. This is because they didn’t know the routes that migrating smolts took. It has taken about 40 years to actually decide to try to find out. Yet, in all this time, it has been possible to take an educated guess and predict where salmon smolts swim, yet no-one seems to have bothered.

My understanding is that whilst the data about mortality is questionable, the AST’s Moray tracking project has thrown up an observation which seems to confirm how to predict migration routes from the comfort of a desk rather than spend £750,000 doing so. It might be expected that fish migrating out of the rivers along the north shore of the Moray Firth might turn up the coast and head up along the coast and out to sea. Rather surprisingly, they didn’t. Instead, they headed south across the firth to join the fish from the southern shore rivers before swimming out along that coast to the sea.

A clue to why the fish do this is apparent on a Marine Scotland map (https://www2.gov.scot/Publications/2011/03/16182005/25), the relevant part of which is shown here.

What the arrow shows is a current that flows southerly across the firth and then out to sea. My guess is that the fish are simply hitching a ride on the current to reduce the effort required to reach the feeding grounds. This makes sense as migrating birds do exactly the same with winds and thermals.

Unfortunately, for east coast smolts, the main pattern of ocean circulation around the UK means that most currents head in a southerly direction down the east coast. The full map of currents around Scotland provides a wider picture of where the currents are headed.

The white arrows show the Atlantic circulation whilst the green ones represent coastal circulation. A closer look at the coastal circulation shows that there are a number of currents on which migrating smolts can hitch a ride including one current which will flow right through the proposed arrays.

However, clearly smolts could swim on other currents around the west coast of the Outer Hebrides. I suspect that which currents are used depends on local conditions at the time of migration and might change from year to year.

Interestingly, an Irish study using arrays has just published some of its results (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YcQmwM3QCno). It can be seen from the Marine Scotland map that there is a current that runs up the north east coast of Ireland. The Irish study shows that the smolts follow the current north.

The big question, given that the announcement of the west coast tracking project was made at a meeting that demanded that salmon conservation should be a national priority, how does this information actually help safeguard wild salmon across Scotland. I believe that it doesn’t.

According to Fisheries Management Scotland, Scotland’s salmon stocks are in crisis. Decisions need to be taken now as to how to prevent the crisis getting worse. Running an expensive experiment on the coast with fewer salmon stocks is not going to provide the answers as to help the stocks of the Tweed, Tay, Spey and Dee, let alone rivers such as the Forth and the Don.

What struck me most on first reading of the Press Association release was the terminology as to how the wild sector describe themselves. The first paragraph begins that ‘Fisheries experts are calling for salmon conservation to be treated as a national priority’. Surely, if these experts were such experts then they would have never let salmon stocks decline to the level they have. The third paragraph begins ‘Conservationists will meet politicians at the Scottish Parliament’. The definition of conservation is the protection of animals from the damaging effect of human activity and that includes fishing.

The truth is that however the wild sector prefers to portray itself, this is all about fishing for salmon. It is the conservation of salmon so anglers can catch them and despite all protestations otherwise, angling is inherently damaging to stocks of wild fish. As I have repeatedly written, the wild fish sector always looks to others to act as scapegoats but actually, the buck stops with them. The day this issue of reLAKSation is posted is also the same day that the new fishing season opens on the River Helmsdale. The River Tay opens for fishing on Wednesday the 15th. The Ness Fishery Board posted a video of a female salmon prospecting for a spawning site only last week. https://twitter.com/i/status/1214291823860027392 Why, when fish are still spawning, are Scottish rivers open for anglers?

These are the questions that the sector should be asking not spending large sums of money on their continued witch- hunt against salmon farming. It is only necessary to look at the catches from the west coast River Carron to see that salmon farming is not the issue. For far too long the wild sector has failed to address the real issues. If they want salmon conservation to be a national priority then they need to start treating it like it is.

As a start why not call for mandatory catch and release and why not a standard fishing season across all rivers in Scotland. In order to give salmon a chance, I would suggest that this should run from 1st May to 30th September. This way salmon rivers will have the greater part of the year free from human interference.