Extinction: Critics continue to claim that stocks of wild fish in rivers within the aquaculture zone are heading towards extinction, if they are not already extinct. The Scottish Government have just released the proposed conservation limits for salmon rivers for 2020.

The proposed gradings will mean that in 2020 there will be 36 rivers classified as category 1 (48 in 2019), 34 (30) category 2 and 103 (95) category 3.

They say that 2 rivers have raised their grade by one category i.e. from 3 to 2 and from 2 to 1 and 24 have seen their grading fall although our calculation makes the number to be 25.

The Scottish Government have not broken down the gradings by area but as there is so much criticism of salmon farming, we, at Callander McDowell, believe that it is worth a look. We calculate that 12 rivers or fishery districts in non-farming areas have seen their grading fall. This equates to 17% of rivers in these areas. By comparison, 13 rivers/fishery districts in the aquaculture zone have seen their gradings falls. This equates to 11% of all rivers in this area. This suggests that more rivers in non-farming areas have been downgraded than in area with farms.

What is more interesting is that the two rivers that have improved their gradings are within the aquaculture zone. The River Moidart has seen its grading improve from a 3 to a 2. The River Gruinard has raised its grading from category 2 to category 1.

So much for extinction. In the light of this information, it is clear that some of the rivers in the aquaculture zone are moving in completely the opposite direction to that of extinction

We suspect that we are a bit of a lone voice, but we will continue to confidently argue that salmon farming is not the villain as anglers would suggest. Improved grading of some rivers in the so-called aquaculture zone would appear to support our view.

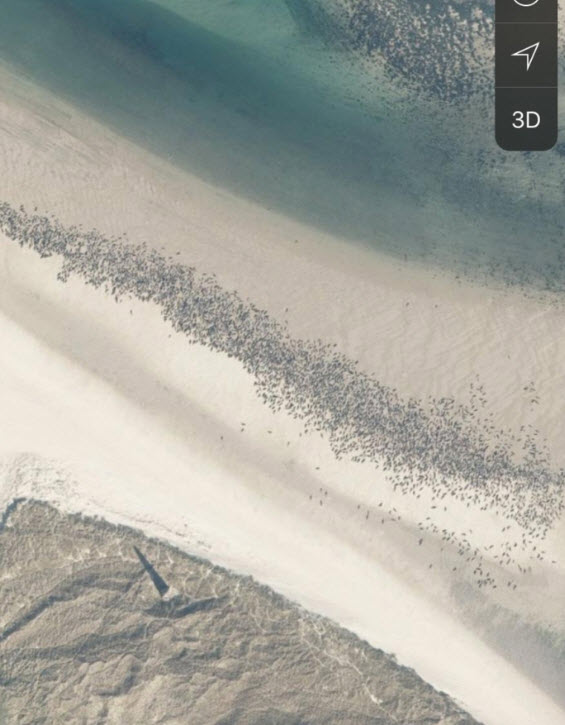

What’s the catch?: The ‘Tweedbeats’ website has posted an aerial picture of the sands around Holy Island on the Northumbria coast showing hundreds of seals. The sands are about 10 miles south of the River Tweed estuary. They say that the Wildlife & Countryside Act of 1981 has led to a proliferation of predators and this has now reached crisis point. These seals are thriving in such uncontrolled numbers, probably at the expense of many of their prey species, and especially Tweed salmon.

‘Tweedbeats’ relates that the ‘late great’ Ori Vigfusson, who established the North Atlantic Salmon Fund (NASF) to protect wild salmon (for anglers) that the only good seal is a dead seal. Critics of the salmon farming industry regularly make out that it is salmon farmers who are to blame for shooting seals, but wild fisheries shoot seals too. This year 27 licences were granted to salmon farms but a further 17, which no-one seems to want to talk about were granted to protect rivers and estate fisheries. Why is it that these licences are not subject to scrutiny in the media too? The Scottish Government website shows that at least seven seals have been shot this year in the East coast and Moray Firth regions. These have not been shot to protect salmon farms.

However, numbers of seals shot to protect salmon farms and wild salmon fisheries are nothing to those killed as bycatch from commercial fishing. This week, our attention was drawn to a report from the Sea Mammals Research Unit at St Andrews University. This comes from the Special Committee on Seals, SCOS, a group who provide government with scientific advice on matters related to the management of seals. This advice is given annually and their reports dating back to 1990 are available on their website.

The latest report (2018) states that the most recent estimate of seal bycatch from commercial fishing is 572 animals. It should be stressed that this is an estimate, however it makes the number that are killed by shooting pale into insignificance and yet not a word about this bycatch from any of those who think nothing of criticising the salmon farming industry.

As we regularly point out, it is not what the salmon farming industry does that attracts criticism, it is simply enough that it is salmon farming to be criticised.

It’s not academic: Benjamin Kao, an intern with the Scottish Aquaculture Innovation Centre, writes in Fish Farmer magazine that he had his eyes opened listening to academics discuss cutting edge aquaculture at the annual ARCH-UK Science event held at Stirling University. He said that this was an important event as it enables various stakeholders in the aquaculture industry to come together to discuss collaboration opportunities and industry trends. Mr Kao says that it became increasingly clear to him as he listened to the various presentations that marketing and perception are among the top of the industry’s concerns going forward.

There were two presentations given about consumers. One was from Ally Dingwall from Sainsbury’s and another from independent marketeer, Karen Galloway. Mr Kao learnt that fish is seen as primarily middle class. It is also more expensive with other proteins being cheaper and perceived to be more filling. Many consumers believe that fish is less convenient to prepare and leaves a lingering smell. Consequently, consumers are more likely to choose to eat fish out of the home rather than as part of their daily diet. Finally, Mr Kao heard that UK consumers have clear favourites when it comes to the species they choose to eat.

Mr Kao concludes that many consumers select price and convenience over quality and health and that it will take a concerted effort for cultural changes to occur. He suggests that this presents new opportunities for the aquaculture industry to help influence UK seafood consumption which would be reflected in greater collaboration between the industry and academia.

Whilst many consumers select fish based on price and convenience, many more never select fish and seafood to eat at home. Quality, whatever that means, and health are minor considerations for consumers if they choose to buy fish at all. This is the fundamental issue affecting fish supply however, it is one that is not a priority for salmon farmers. This is because, unlike a lot of fish and seafood, demand for salmon is relatively strong. This is because many consumers do not necessarily perceive salmon as fish. In fact, salmon now warrants its own category like beef, chicken, pork and lamb rather than being classified together as fish.

Thus, the issue of consumption may not be high on the farmed salmon agenda unlike the wider fish and seafood category. The days for further research about fish and seafood consumption are long gone. The facts about the market cited by Mr Kao are well established and are often repeated as Mr Kao has highlighted. We know the many reasons why consumers are not buying fish and seafood; the challenge is how to reverse this trend. This challenge is getting harder and harder by the day. That many supermarkets are now closing, or downsizing fish counters is not helping but this is understandable if consumers are not buying fish from them. It is inevitable that these counters are becoming redundant. The move way from large supermarkets to smaller more convenience stores also plays a part as these smaller stores can only stock limited ranges.

We, at Callander McDowell, don’t see smaller ranges as a problem. UK consumers prefer just five species so we should encourage their consumption. Unfortunately, those advocating sustainability want to see a wider choice, but all this does is deter consumption further. As we have written previously, the issue of sustainability has probably increased the rate of decline in consumption more than anything else.

Mr Kao wants to see closer collaboration between industry and academia to help promote greater consumption. We would argue that the time for research is long gone. Instead, what is needed, is action.

Fish is food: Blue Planet Society, a group campaigning to end overexploitation of the world’s oceans, is often critical of salmon farming, however, it seems that their latest target is other marine conservation organisations.

Blue Planet Society say that the Good Fish Guide, The Sustainable Seafood Guide, Seafood Watch and others all promote the consumption of the sustainably produced/harvested fish they purport to conserve. They say to think of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) producing a Good to Eat Bird Guide and you’ll understand why this is a problem. They claim that fish are so inextricably associated with food that even the people charged with their protection can’t separate their exploitation from their conservation.

In the UK, cod, haddock, mackerel and tuna are likely to be the only wild animals most people will ever eat. According to Blue Planet, consumers are eating these fish to extinction. They say that we must start to think about these fish in a different way. Instead of being food, we must recognise these fish as wildlife.

The problem for us at Callander McDowell is that even if we consider fish as wildlife, they are still food, if not for us, then as part of the natural food chain. We, humans are also part of that food chain and whilst we have opted not to eat some animals, we do eat others. That’s simply what we do.

The question for Blue Planet is where do we draw the line? The reality is that it is not about reducing our overall consumption that needs to be addressed. It is that there are simply too many humans on the planet, and it is our numbers that need to be controlled not what we eat.

It has occurred to us that Blue Planet’s comments about marine conservation organisations that promote the consumption of the fish that they want to protect applies to other areas of interest.

It could also be said that the wild fish organisations that promote salmon conservation also promote their exploitation. In fact, the only reason for conservation is that they hope that there will be more salmon available for them to catch and kill.

No Kitchen: The Times newspaper reports that in most households, the kitchen is the space on which most money is invested when renovating and considerable time is spent admiring other people’s kitchens on social media.

Manchester, our local city, is awash with cranes which are an indication of the scale of investment in new buildings. Many of these new developments are not for sale. Instead they are ‘build to rent’. These blocks of flats, funded by financial institutions, are the residential equivalent of WeWork offices with communal spaces, sitting rooms or bars where tenants can socialise. They also include launderettes and gyms. The facilities include super-fast wifi which is part of the rent. One feature of these flats is that they lack a proper kitchen. This is because the new Gen Z tenant is more likely to order food via Deliveroo than go shopping for food.

Surely, this is another nail in the coffin of home cooked food. Younger people growing up with Deliveroo are unlikely to change their habits as they grow older. Is it possible that in another forty or fifty years, all food will be delivered ready to eat and that retail grocery will have disappeared forever? Of course, by then, eating fish may have been consigned to the history books.