Vitamin deficit: In the last issue of reLAKSation, we featured an image of a wild fish that had been caught by an angler in Norway that showed signs of disease. We have since found other images of similarly affected fish from not just Norway, but also Scotland and Ireland. We have also come across an account from the Norwegian Veterinary Institute in which they detail the analyses they have done to try to identify the cause of the disease. This is made more difficult because the fish are also suffering from secondary infections of fungus and sea lice. As might be expected, the angling fraternity were initially quick to blame salmon farming for the appearance of these fish.

However, there have been several reposts saying that this problem is nothing to do with salmon farming at all. One of these comes from scientists working in the Baltic who have also seen fish exhibiting the same outward appearance. They have also been concerned about other species of animals that are suffering similar problems. The common factor is that a possible deficiency of the vitamin thiamine compromises the fish’s health by reducing the immune system leading to some of the symptoms observed in fish caught recently in European rivers.

However, of even greater concern is that during the late 1980s Lennert Balk, an environmental scientist, then of Stockholm University, discovered that several species of fish including Atlantic salmon were unsuccessful in their attempts to reproduce. Many of the resulting larvae failed to swim in a straight line and were generally lethargic before dying. After some attempts at trying to uncover the source of the problem, Dr Balk gave the larvae a supplement of the vitamin thiamine and almost all survived, whilst a control batch without the vitamin all died. His conclusion was the fish were suffering a thiamine deficiency.

A similar observation was made by researcher John Fitzsimons, then a Canadian Government fish biologist who found lake trout and some species of salmon were failing to reproduce and had difficulty with their balance. He said it was like the fish were drunk. After some trial and error, he too provided a supplement of thiamine and found that the problem was resolved. He also concluded that the cause of a population decline in the Great Lakes was down to a thiamine deficiency.

Later, another group of researchers found that the Lake trout and salmon were mainly eating a diet of alewives, an invasive species of fish that is rich in the enzyme thiaminase, which breaks down thiamine. When they fed fish a diet just of alewives, they found that the eggs contained just 20% of the thiamine of eggs from fish that had been fed a different fish. They concluded that a deficiency of the vitamin thiamine stopped all reproduction in some fish species causing huge population declines.

The syndrome associated with thiamine deficiency has been named M74. In the Baltic, the syndrome has been found to be linked to variations in the local sprat and herring populations which form the basis of much of the salmon’s diet. Both sprats and herring contain thiaminase so when the fish gorge themselves on these species, the stomach is unable to denature all of the enzyme which results in the destruction of thiamine in the salmon which in turn compromises the fish’s ability to reproduce.

Wild fish are often diseased but are rarely seen. Weak and sick fish usually succumb out of sight and thus it is only if there is a major outbreak that concerns are raised, such as is happening now in Norway and elsewhere. For example, the River Tweed authorities (a river as far from salmon farming as it is possible to be) have issued a warning to anglers to watch out for diseased fish. Yet, it is not the disease which we think is the major issue here. Instead, we wonder how much this dietary deficiency is implicated in the overall decline of wild fish in recent years. Again, we can only suggest that whilst the main attention is focused on salmon farming, the blindingly obvious is being missed.

Wildly concerned: The BBC news website reports that due to increasing concern about the impact parasitic sea lice are having on wild fish stocks, the Scottish Rural Economy Secretary, Fergus Ewing, has announced that salmon farms will have to report level of sea lice on a weekly basis. The BBC say sea lice have been blamed for falls in the number of wild and farmed salmon in Scottish waters. They refer to the Panorama TV programme which described how wild fish in one loch were essentially eaten alive by the parasites.

Sadly, the Panorama programme didn’t investigate the allegations but simply reported that the wild fish lobby blamed local salmon farms for the deaths. However, as we well know. the real problem in the Blackwater was that the fish suffered extensive sunburn and then succumbed to secondary fungal and sea lice infestations. As we have previously discussed the local representatives refused to discuss the deaths because they feared that their claims would be obfuscated. If they had been so sure that sea lice were the primary cause of death, then they had nothing to fear by engaging in open discussion.

Whilst the BBC say that there is increasing concern about sea lice, there is little evidence to support these concerns. The wild fish lobby ignore the fact that many rivers in the Aquaculture Zone are now category 1 or 2 and therefore of such a conservation status that anglers could kill any salmon they catch. If the situation was as bad as claimed, all west coast rivers would be category 3 and they are not.

The BBC state that that Mr Ewing has said that the new rules will mean salmon farms will be more open and transparent and provide much more detailed information. However, what he didn’t say was how these new rules will result in the return of more wild fish to west coast rivers because our view is that any improvements in the management of sea lice, however welcome, will do nothing to improve the conservation status of salmon and sea trout within the Aquaculture Zone simply because salmon farming isn’t the issue. It’s just the scapegoat.

The Wild Trout Trust have blogged about their attendance at a workshop in Wester Ross, during which attendees participated in a sweep netting at Gairloch. They discuss two fish which they had caught. The first sported an infestation of around 180 lice of varying life stages, which they say was pretty alarming. The second had an estimated 500 lice, which they say is potentially fatal. They suggest that the fact these two trout were captured in a sea loch tens of kilometres from the nearest salmon farm demonstrates the potentially far reaching impact of cage farming on wild fish populations.

The photo accompanying the blog shows a very thin sea trout which didn’t look infested. The WTT will undoubtedly say that the fish was thin because of the lice infestation whereas the probability is that the fish was thin due to poor feeding or sicknesss and has succumbed to secondary infestation by lice. The question is whether these two fish reflect the sea lice status of the rest of the sea trout population or were they the weak fish that happened to be unable to avoid the net.

We have mentioned previously that sea lice, like all parasites will infest a few fish with high numbers whilst the majority remain free of the parasite. This is called aggregation and is basic biology, yet it is something that even the most senior scientists working in this area appear to ignore as it doesn’t support the claims against salmon farms. As interactions are never openly discussed, there is never any opportunity to discuss it face to face.

By coincidence, NASCO held a symposium in Tromsø this week. This was to discuss ‘Managing the Atlantic salmon in a rapidly changing environment – Management challenges and possible responses. The programme covered a wide range of issues including aquaculture. In fact, three of the talks concerned aquaculture and whilst Tromsø is located in the heart of the Norwegian salmon farming industry, there was just one person connected to the industry in attendance from Norsk Industri. Another participant in the symposium has told us that the lack of any industry people at the meeting was reflected in the absence of open and honest discussions. This is something to which we whole heartedly agree. Our experience of NASCO is an unwillingness to discuss the issues. If the wild fish lobby are so sure that salmon farming is the cause of the problems for wild fish, then they should be willing to discuss the issue openly and honestly.

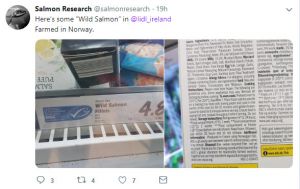

Salmon Research: By chance we have just come across and example of the fact that objective knowledge decreases with increased self-assessed knowledge. ‘Salmon Research’ the anonymous blogger (although his identity is common knowledge throughout the aquaculture industry) has tweeted pictures of salmon that is labelled as wild but supposedly has been ‘Farmed in Norway’. His pictures were taken in Lidl in Ireland.

The first picture shows a shelf label that states: ‘Ocean Sea wild salmon fillets 500g 4.85’ (presumably euros). The pack on the shelf is upside down but the words ‘Salmon in Puff Pastr(y)’ are visible as are a couple of packs of prawns.

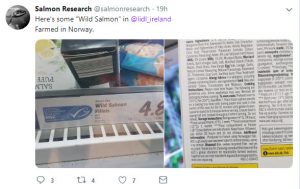

The second picture is of the side panel form a pack, which includes product description, ingredients, cooking instructions, storage instruction etc. The description begins (in bold letters) ‘Salmon fillets formed from blocks of boneless and skinless salmon wrapped in puff pastry with a creamy dill sauce.’ The panel also highlights that the ‘salmon is Salmo salar and is farmed in Norway.’

Now it doesn’t take anyone with specialist research experience to recognise that the shelf label does not refer to the product displayed. This is not an uncommon occurrence in retail outlets and is one that will be familiar to most shoppers, although seemingly not to anti-salmon farming bloggers.

This should be blinding obvious from the pack weight which for the packs of wild salmon is 500g whilst the DeLuxe salmon in puff pastry weighs in at 700g (£3.99).

To help Salmon Research, we have included a photo of a pack of MSC Ocean Sea wild salmon fillets. It certainly doesn’t come surrounded by puff pastry. We can only hope the rest of his research is more thorough than this.