White paper: Thursday afternoon saw the Norwegian Fisheries Minister outline the new white paper on aquaculture. It will take me a little time to digest the plans the Norwegian Government have for aquaculture, but it is clear from just a quick look that the major focus is on sea lice.

Unfortunately, the Norwegian Government view on sea lice is swayed by the usual narrative put out by scientists at Vitenskapelig råd for Laksesforvaltning and the Institute of Marine Research with encouragement from the wild fish lobby.

Both Kyst.no and ilaks.no have published an identical list of the reports proposals so I guess they come from a government press release. The second point is that:

The Government will regulate aquaculture activities based on actual impacts.

Yet, when it comes to sea lice, there is no evidence of any actual impacts, they are all conjecture based on models and an outdated narrative.

One of the proposals in the white paper is to move away from the Traffic light System to a system of lice quotas. There is no clear explanation of why the Traffic Light System is to be abandoned but it is important to ask why. The answer is simple. The science of which the Traffic Light System is flawed so the Traffic Lights were never going to work. A system of sea lice quotas based on the same flawed science is unlikely to offer a better solution than the Traffic Light System it will replace.

Isn’t it time, the salmon farming industry stood up and demanded actual proof of the alleged damage, The fact that 42 rivers in Norway are now subjected to fishing controls is not evidence of damage by the salmon farming industry.

Wicked: A recent FOI request highlighted three new papers relating to sea lice that were just published or in the process of being published. I was intrigued by one that appeared in the journal Socio-Environmental Systems Modelling, not an obvious journal for sea lice science. The paper about Knowledge Strengths is a collaboration between the the Scottish Marine Directorate, the Institute of Marine Research in Norway, Firum from the Faroe Islands and the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency. The inclusion of SEPA is somewhat surprising as they have made it clear that they are not interested in discussing the science behind the Sea Lice Risk Framework, yet now appear to be involved in scientific research.

When I saw the paper, I realised that it was slightly familiar, and this was because its ideas were presented at the MASTS conference in Glasgow towards the end of last year. When I say it was familiar, I can’t say that I actually heard much about the theory as the presenter mumbled through most of the presentation.

The abstract of the paper begins by saying that policy developments for a sustainable Blue Economy require scientific advice and modelling is a valuable source of that advice especially in relation to the important salmon farming industry, the development of which they say is limited by salmon lice infestation. However, whilst modelling is a valuable source of advice there are inevitable uncertainties and from my point of view one such uncertainty is the failure by any research scientists to find sea lice in any number, let alone the numbers predicted by the models. This is something none of the modellers or scientists appear willing to discuss. The absence of sea lice from this equation appears to be a minor inconvenience.

Whilst the papers raise a number of issues that I could discuss here, I would like to focus on the beginning of the third paragraph of the conclusions section.

“When dealing with complex and wicked problems, uncertainties can be used by stakeholders to influence decision making”.

Wicked? When did sea lice become a wicked problem?

I have to admit that I hadn’t realise that wicked problems are an actual thing. The phrase was originally used in social planning or social engineering to influence particular attitudes or social behaviours. It was first defined in 1967 by the American philosopher C West Churchman, who wrote that ‘The adjective ‘wicked’ is supposed to describe the mischievous and even evil quality of these problems, where proposed solutions often turn out to be worse than the symptoms.’

I would mention again that it is the authors of this paper that use the term wicked, and it seems they have it absolutely right that sea lice are a problem where the solutions are worse than the symptoms. This is because the symptoms are described by a model that bears no relation to reality. As I highlighted, if the model is to work, then sea lice have to actually be present. At the moment, the Sea Lice Risk Framework is based on the assumption that sea lice are where the models predicts but after thirty years of attempts to find these lice, they still remain elusive. The conclusion of the Scottish Government’s SPILLS project says that just because they couldn’t find any lice doesn’t mean that they are not there. Actually, it does.

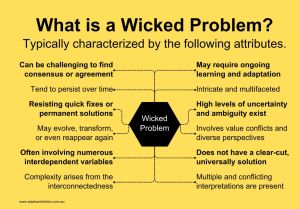

A modern definition of a wicked problem is that ‘Wicked problems are complex multi-faceted social or environmental issues that are difficult to define and solve.’ They are referred to as wicked because they are characterised by a number of unique attributes that make then challenging to address. A summary chart of the attributes is shown here.

As I said it is the author of this paper, including someone from SEPA that have defined sea lice as a wicked problem and although wicked problems are challenging to address, SEPA has made the solution so simplistic that it is doomed to fail.

However, what is really wicked about this wicked problem is the refusal of both SEPA and the Marine Directorate to impose their solution on the industry without any proper discussion of the science and their inability to answer such fundamental questions as to where are these lice larvae?

Of course, this issue is not restricted to Scotland and the same questions can be asked about the Traffic Light System which we already know does not work, primarily because the lice are not present in the fjords as predicted but also because ethe science shows sea lice are not responsible for the claimed impacts on wild fish.

Horse to water: There is an old saying ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink’. I am reminded of this saying after reading the exchange of views between Øyvind Haram, Communications Manager at Seafood Norway and Jørgen Christiansen former Communications Director at Marine Harvest in the pages of ILAKS.

This concerns the industry’s new campaign with arguments for and facts about salmon farming – https://sjomat.no/ . Jørgen Christiansen wrote that it is well written and those who put it together should be commended. However, he is not so positive towards those who commissioned the campaign for he says the campaign has more in common with advertising than communication. Jørgen says that the industry should be talking with the public not to them.

However, as Øyvind Haram points out the campaign includes TV advertising, something the industry does not do often. He said that the sector must become better at telling the public what we do with honesty as a key word. The goal is to showcase both the challenges and the opportunities in salmon farming because there are plenty of people who never hear the good things we do, just the negatives,

Regardless, of both these opinions, my view is that there is an element of both views that are right however, I take a very different approach. Yet before I outline the issues from my perspective, I would just like to mention one way promoted as an approach to ensure consumers were better informed about the food they eat. This is the use of QR codes on packs. The idea was that rather than cram as much information on packs, the QR code could be scanned taking the shopper to a website such as https://sjomat.no/ I recently looked round a number of retailers to find examples of such QR today. It was a struggle to find more than a handful of examples, and this is because QR were dropped because shoppers never bothered to use them. They simply weren’t interested in the detail.

This new campaign is ultimately in response to the Norwegian reputation survey that has found salmon farming’s reputation amongst the public is at the lowest it has ever been. The industry is right to feel that it should provide a balanced view of the industry to help reclaim some its lost reputation. However, as I said at the start, it is easy to put their material in front of the public, but it is a very different thing to make them absorb it and understand what it means. I know from my own experience how difficult it is to break through the barriers. Even the most detailed and thorough analysis of data showing that salmon farming is not responsible for an impact on wild salmon is met with responses saying that as someone involved in the aquaculture industry I would say that and therefore anything I say can be dismissed as industry propaganda. This is probably what the public response will be to this new campaign.

In the middle of his commentary, Jørgen Christiansen hits the nail on the head. He says that it is important to distinguish between problems and the underlying challenge. He uses disease to illustrate his point saying that when the industry responds to negative publicity with an information campaign, it is treating the symptoms. However, treating the symptoms can mean that the underlying disease is ignored. Jørgen says that it is the challenge (the disease) that must be dealt with, not the problems (the symptoms).

For me, the big question is why does salmon farming have a bad reputation? The immediate answer as appears in various commentaries is the high level of mortalities and allegedly poor welfare. However, they are only reasons why the industry has a bad reputation, it doesn’t explain how the public are aware of the reasons and how they come to believe that high mortality etc equates to a poor reputation. I can’t say for Norway, but certainly other sectors can also experience high mortality, but they don’t suffer from a poor reputation. In the UK, chicken could suffer from welfare issues, mortality and environmental concerns, not forgetting the spread of bird flu. Yet fried chicken shops and now wing stops proliferate. These are staple foods of the younger generations.

The question is who or what is driving the negative publicity about salmon farming that has resulted in such a poor reputation. The answer is not hard to find because it is common to salmon farming wherever salmon farms operate and that is the wild fish sector. Based on a long established, but unproven, narrative, they blame salmon farming for the decline in wild fish numbers. They feel that the best way to address this problem is to make as much noise in the media as possible, irrespective of which aspect of farming they highlight.

The two big topics are mortality and sea lice. Round 2017/8 mortality was never an issue. It became one because one of the wild fish representative groups felt that their attempts to persuade the public to take action by avoiding farmed salmon to safeguard wild salmon had failed so instead, they thought that focussing on an industry issue such as mortality might deter consumers from eating farmed salmon. Whilst consumers continue to eat farmed salmon, the issue of mortality has reached the politicians and the press, and the outcome is a negative image of the industry.

The obvious question is why mortality is so high, and the answer has been highlighted by the Norwegian Veterinary institute as being the repeated treatment of farmed salmon for sea lice. This leads to the next question as to why farmers are treating so much, to which the answer is that the regulators have set an ultra-low level for lice infestation on farm in order to protect wild salmon from infestation and death.

This is where the questioning becomes muddled because the science and evidence do not support the narrative that sea lice associated with salmon farms are responsible for the current crisis in wild salmon. The wild fish sector in Norway says that the Norwegian scientific community are convinced that salmon farming is having an impact on wild salmon. This is the heart of the matter concerning reputation.

Whilst the industry hopes its investment in TV advertising will help improve the reputation of farmed salmon, the reality is that until the scientific community is confronted to prove categorically that salmon farming is the cause of wild salmon’s problems, the issue of reputation will never be fully addressed.

Certainly, sitting round a table with the scientific community is a lot cheaper way of addressing reputation than TV advertising.

Hire a professional: I was gripped by a commentary written by Johann Martin Krűger, the industrial policy advisor at Norwegian Seafood Companies. He related that he had heard the Minister of Agriculture & Food use an expression which he had not heard of. It is that ‘if you want something done, talk to someone who can’.

Johann says that this relates to the question of who will steer the future development of the seafood industry. The implication is that it is people who are within the industry who are best qualified to do this. This reminds me of a BBC TV programme from 1995 called Sid’s Heroes. Sid was a management consultant, but one unlike any other. He did not give advice but suggested that the people best qualified to ensure a business operated most effectively were the people employed in the business and not the managers but those who actually did the jobs. They had the best understanding of the processes, and this was certainly borne out in the TV programmes about six different businesses, which in every case saw massive improvements. Sadly, in every case, the management reverted back to the old ways presumably to assert their authority.

However, the point remains the same that if Norway wants to remain a leader in seafood production, then it must depend on the expertise of those within it. Johann refers to the various research institutions which are researching everything and anything that might help the sector develop but points out that much of the research ends up in a paper tray. This is because of the lack of interaction between research institutions and the business community.

This rings a bell because my experience is that the research institutions seem extremely reluctant to engage outside their own circle. I appreciate that my experience relates to sea lice research, but Johann suggests that areas such as fish biology, technical soliton and new feed ingredients suffer from a lack of interaction. He says that when business is invited to become involved it is usually at the last minute and after decisions have been made.

Yet, I was most surprised to see the programme for the Norwegian Seafood Council’s Paris 25 meeting that took place this week. This was much more extensive than the similar event held in London earlier this year. The Paris meeting included presentations with a heavy focus on the seafood sector but what surprised me most was the section on innovation which included a talk on the future for aquaculture in Norway, the challenges and possibilities. Rather than listen to the words of an expert from the aquaculture sector, the audience was treated to the views of Marfi Skuggedal Myksvoll from the Institute of Marine Research, who the Institute describes as a young talented scientist who has made her name for herself with research including the environmental effects of fish farming. She is an oceanographer who works with advanced models, similar to those that predict weather forecasts. For example, the sea lice model is an example of such a ‘weather forecast’ which calculates the spread of sea lice along the coast. She says that the model is an important contribution to the Traffic Light System which the Government use to regulate aquaculture. A description can be found at https://www.hi.no/hi/nyheter/2020/oktober/framtiden-lakselusmodellen

We now know the Traffic Light System is inherently flawed as is much of the science used in its calculation. If a researcher who advocates the Traffic Light System is commissioned to speak at a meeting about innovation and the challenges for aquaculture. I hold little hope for the future of the industry. Perhaps, the Norwegian Seafood Council should have followed the advice of the agriculture minister and found someone who was an expert on aquaculture not someone whose expertise lies in scientific papers.