Happy Christmas: This is the last reLAKSation before Christmas. I would therefore like to wish everyone a very merry festive season and a wish for a happy 2022.

There are a number of issues I wanted to discuss in coming issues of reLAKSation but the timing of the holiday season with both Christmas and New Year occurring over weekends means that I am unlikely to explore them until January, by which time they may be old news. Instead, a brief mention of some of the issues follows:

- Salmon farm industry critics always highlight in relation to salmon mortality that the public would never tolerate any excessive mortality if they occurred in conventional agriculture. Yet, according to poultry magazine, Britain has been hit by the largest ever avian influenza outbreak with 36 cases confirmed so far. The country’s chief vet told BBC radio news that over 500,000 birds had been culled as a result. The Food Standards Agency have said that on the basis of current scientific evidence bird flu poses little risk to UK consumers and that properly cooked poultry is till safe to eat. Public concern is so high that the story hasn’t even reached the mainstream press. Yet again, the farmed salmon industry critics are proved wrong.

- Congratulations to the Array Collective, a group of artists from Belfast for winning the Turner Prize. They beat the London based duo Cooking Sections, who failed to understand that all salmon are grey in colour until the fish eat food containing carotenoids. Hopefully, in future their art will be based on fact not ignorance.

- About three years ago, S&TC concluded that they were unable to influence consumers to avoid farmed salmon to help protect wild salmon so that anglers would have more salmon to catch and kill, they have reverted to their former message this Christmas to help raise funds. Visitors to their website would have been greeted by a large banner urging everyone to say no to farmed salmon this Christmas. S&TC say that anyone buying farmed salmon is supporting an industry that endangers wild salmon and sea trout. Saying no to farmed salmon gives wild fish a break, yet this desire to give wild fish a break doesn’t appear to extend to saying no to angling. The new season starts on the River Helmsdale on January 11th in just three weeks’ time, when some fish may still be spawning.

- A new paper from Norway argues that the methodology for estimating mortality due to sea lice used in the Traffic Light System systematically overestimates the level of mortality.

- The Norwegian Committee for Salmon Management have published their latest report on the status of wild salmon in Norway. Unsurprisingly, it is much the same report as last year’s with a date change. Salmon farming is still considered their greatest threat. The entry about sea lice is unchanged. “In 2010-2014, we estimated that 50 000 fewer salmon returned from the ocean to Norwegian rivers each year due to the impacts of salmon lice. For 2018, we estimated a reduction of 29 000 salmon due to salmon lice, and for 2019 a reduction of 39 000 salmon.” What about the numbers for 2020? And as I regularly point out, anglers kill around 100,000 salmon each year in Norway so why is this not considered a greater threat than the (over)-estimated 29,000 fish loss to sea lice.

- Alexandra Morton has suggested an open panel discussion to discuss why her findings on sea lice are different to those from others. In my opinion, such meetings descend into farce because those opposing salmon farming drown out any reasonable debate. It was exactly such a meeting that led me to start my own investigations into wild farmed salmon interactions. I would suggest that if Ms Morton wants validation of her findings, she should present them at the best forum available which is Sea Lice 2022 which takes place in May in Tó I am sure she would be very welcome.

- The Seafood Watch programme has presented their latest listings. The presence of farmed salmon in the red list is of no surprise since the combination of the current transparency of many farms together with outdated preconceived views is all that is needed to justify why farmed salmon are not considered the best choice for consumers. Fortunately, many consumers ignore such advice recognising that farmed salmon is the best choice for taste and value.

I plan to publish an edition of reLAKSation between Christmas and New Year – probably on Wednesday 29th. This will be a snooping special.

Wild Fish Strategy: If I remember correctly, the Scottish Government’s wild fish strategy was supposed to be published a year ago, but the pandemic and other problems have meant that according to the working group’s latest minutes, publication is due before the end of the year. Given the past delays, I wouldn’t be surprised if it doesn’t appear before 2022.

Information about the machinations of the group has been thin on the ground. An expected website never appeared, and I have had to request copies of the meeting minutes even though there has been no public information of when meetings have taken place.

My own view of the strategy is that when it is published it will favour wild fisheries interest more than wild fish. One of the mainstays of the strategy is a new pressure mapping tool developed by Marine Scotland Science which will identify where manifestations of each of the pressures exists. The problem with this tool is apparent from the title page of the user guide http://fms.scot/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/191206-Mapping-Atlantic-Salmon-Pressures-in-Scotland-Mapping-Tool-Step-by-Step-User-Guide.pdf . This states- step by step guidance for District Salmon Fishery Boards and Rivers/Fisheries Trusts – all people who are involved in wild fisheries. I don’t suppose legal exploitation will feature heavily on the map, but I expect salmon farming to dominate the west coast, even though it is more than apparent that salmon farming is not the threat that the wild fish sector claims.

The reality is that salmon farming is just a convenient scapegoat used to divert attention away from the reality that any knowledge of what is really happening to wild salmon is rather thin on the ground.

An article in the Courier newspaper attracted my attention. This was headed ‘Salmon in the Tay are getting bigger – so why are anglers so worried?’

Could it be that they have caught and killed so many fish in the past that they are now worried that there are none left?

Apparently not. The Tay District Salmon Fisheries Board has noticed an increase in the proportion of larger salmon in the river, which the newspaper says sounds like a good thing but unfortunately, the overall numbers of salmon are said to be decreasing. There are now concerns that the number of fish returning to spawn could reach a tipping point.

The newspaper reports that Dr David Summers has spent 30 years studying and managing fisheries. He says that there was no doubt that salmon are spending more time at sea before returning to the Tay. He explains that shifting feeding grounds are resulting in the fish growing more slowly but he says that the average size of salmon is, curiously, actually increasing.

The use of the word curiously caught my eye as especially, like many scientists, I am curious by nature and as I have access to many years of catch data courtesy of the Scottish Government, I thought it would be interesting to see by how much the size of these salmon on the Tay has changed. I also wondered whether the same changes occur across all of Scotland for the period after 2010 when numbers of salmon caught began to crash.

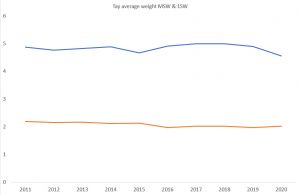

The first two graphs show the average weight of both MSW salmon and 1SW grilse for the Tay catchment and also for all of Scotland.

Both data sets suggest that average weights for larger salmon and grilse have remained relatively constant over the last decade. The data does not support the view that MSW are getting larger in the River Tay or across all of Scotland.

Dr Summers also mentioned that from the 1960s, smaller grilse have dominated catches but now he says the ratio has switched so that, although there are fewer fish, there are more larger MSW salmon in the river.

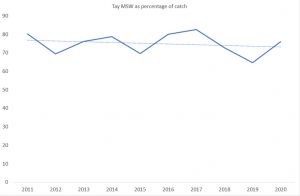

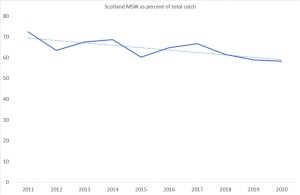

However, the following two graphs show the percentage of larger MSW salmon as a proportion of the total catch, again for the Tay and for all of Scotland.

For the Tay (left) the percentage has remained constant whilst for all of Scotland, the percentage has shown a slight decrease meaning that there are less MSW salmon in the catch rather than more. This does not support the observation that more larger salmon are returning to the River Tay.

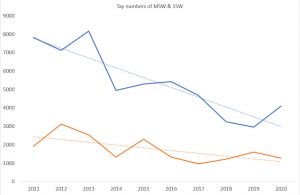

The final set of graphs show the number of large salmon and grilse caught by rod and line from 2011 to 2020. It is clear that the numbers of both MSW salmon and 1SW grilse have dramatically fallen over the last decade.

This is not of any surprise given that even the official MSS catch data shows a collapse in catches since 2011. The question is why has it happened now? My view is that the writing has been on the wall since the late 1980s when catches on the west coast started to show a decline. Most of these rivers are small spate rivers with a relatively small stock of fish which meant there was very little spare capacity once number of returning fish started to fall. By comparison, the number of fish returning to east coast rivers also fell but because the rivers were so much larger, they held a greater reservoir of fish. Over the years, this reservoir has contracted until by 2011, there was no spare capacity left in these larger rivers too, so the number of fish caught consequently declined too. As Dr Summers says this is not a healthy situation. However, for the last thirty years, the wild fish sector has been so engrossed in blaming salmon farming for all their ills, that wild salmon’s wider problems have been largely ignored, especially in trying to understand what is happened to salmon whilst they are at sea.

Meanwhile, these graphs demonstrate that there is still a massive gap in our understanding of what is happening to wild salmon in Scottish rivers. The data does not support the view that there are proportionally more larger MSW salmon coming back to the Tay or to all Scottish rivers. Equally, the weight of the fish has not increased but is staying the same. What the data does show is that fewer salmon are being caught and this is reflected in the fact that fewer salmon returning to Scottish rivers.

The Courier article begins by saying that warming seas are affecting salmon in the Tay suggesting that climate change will be the new scapegoat for declining salmon numbers whereas the decline began back in the 1970s long before the words climate change appeared in our language. The reality is that salmon have been in trouble for decades, but little has been done to even acknowledge the fact. This is why the Wild Fish Strategy needs to be radical and hard hitting, which it never will be. This is because it is more likely to be a Wild Fisheries Strategy.