Seaspiracy: A lot has already been written about this film except the one real issue. Ali Tabrizi expresses concerns about plastics, sharks, whales, forage fish and other matters affecting the marine environment but misses the point. He can argue that we should reduce plastic or that we should stop harvesting forage fish for feed but ignores the fundamental problem. These are all concerns induced by humans. It is not the issues of the oceans that need to be highlighted, but rather it is us that are the problem. There are simply too many of us over-exploiting the world’s resources. If we are not plundering the oceans, then we are ripping up the forests. We simply cannot have it all and eat it. Perhaps, this is the film that Mr Tabrizi should really be making.

Having said that, there was one issue raised during the film that caught my eye but is likely to have gone unnoticed by salmon farming critic, Corin Smith, who is described by Salmon Business as an online betting millionaire and, who featured in the film. This is the concern that over-fishing was having a detrimental effect on marine life such as coral reefs. The film highlighted that overfishing led to a huge reduction in the nutrients that fuelled the growth of the flora and fauna of the seabed. These nutrients arrive in the form of the faecal waste generated by the fish. The loss of fish meant no faeces and therefore no nutrients to maintain the cycle of life and the death of the life of the seabed.

Mr Smith, who was oddly described by Mr Tabrizi as a whistle blower despite never having worked for the salmon farming industry, related how net pen salmon farms produced huge amounts of fish waste equivalent to the waste from 10-20,000 people and that the waste from of the whole of the Scottish salmon industry is equivalent to the waste of the entire population of Scotland.

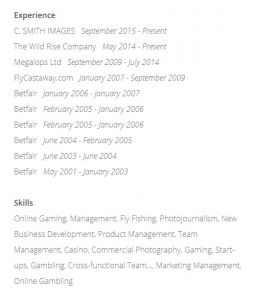

Unfortunately, Mr Smith is not a biologist. He did enrol on a biology course at the University of Edinburgh, but soon dropped out. The following entry comes from the website European Graduates, a database of people who attended university which lists Mr Smith’s experience and skills, none of which relate to salmon farming.

Mr Smith comes to this issue as an angler who blames salmon farming for the decline of wild fish stocks. As he is not a biologist, he happily compares human waste to that from fish even though they are totally different, but more importantly fish waste is part of the natural marine ecosystem. Three and a half trillion fish defecate into the world’s oceans every day. The waste produced from salmon farms is no different. Of course, the fish waste is deposited in a small area, but it does get absorbed into the local ecosystem, which is why there are not mountains of waste under even the longest established salmon farms.

Mr Tabrizi incorporates a graphic in his film to illustrate the amount of waste produced by Scottish salmon farms. He was clearly not advised by Mr Smith that the salmon farming industry can be found just along the west coast because the graphic shows the waste spreading even to the seashore outside Edinburgh. Interestingly, the area around Orkney is waste free, despite being home to many salmon farms.

Like much of the film, this graphic is so misleading and so different to the reality. If all the salmon farms in Scotland, were placed together, they would take up the space of two eighteen-hole golf courses. To put this into perspective, the following map highlights the spit of land outside the town of St Andrews on Scotland’s east coast. This is the home of Scottish golf and the spit of land is covered by five separate gold courses belonging to the golf club. If this district is viewed on an online map and then a wider area is brought into view, the spit of land quickly disappears so by the time the map of Scotland shown on the film is viewed, salmon farming takes up an area less the size of a pin head. It is totally infeasible for the whole of the salmon farming industry to produce waste that covers even a small area of that shown in the video. Mr Smith has completely exaggerated the impact of the waste, let alone understand that it forms part of the natural ecosystem.

Mr Smith comes from the angling sector, and is quick to highlight, but fails to understand, any of the issues concerning the salmon farming industry. This is not surprising. His former employers, Salmon & Trout Conservation Scotland have been criticising the salmon farming industry for years, based on their belief that the industry is responsible for the decline of wild fish. About three years ago, they concluded that their attempts to dissuade consumers to stop eating farmed salmon in order to protect wild fish to enable their members to catch and kill them instead, was not working. They decided to focus their efforts on highlighting mortality levels on salmon farms even though farm mortality has no bearing on wild fish numbers. They thought that images of dead salmon would be more likely to deter consumers from buying the fish in stores.

Mr Smith subsequently extended this brief by swimming out to farms to obtain images of lice infested fish taken by hanging on to the structure and taking photos just below the surface. It is these images that have dominated the negative narrative against salmon farming. In a comment dated 10th February Mr Smith says that he has been to more salmon farms than most salmon farmers, most salmon farm employees, regulators, journalists, scientists and activists, totalling way over 100. He also says that he has spent hundreds of hours diving and filming in the water around salmon farms, yet it is the same handful of images that he uses in the media. None of his photos are date stamped, nor give a location so the assumption is that if he has indeed spent many hours in the water around salmon farms across Scotland, his efforts have not been rewarded with many other examples of similar infested fish.

It is worth pointing out that the few fish in his photos do not represent the majority of the fish in the pens. In the still of early morning, the few weakened fish swim in less frequented surface layers, where they are easily photographed. It might be assumed that they would be also easy to catch and remove but there is a massive difference between taking a photo in the early morning stillness dressed in a dark wet suit and farm staff walking round the pen trying to remove these handful of fish with a hand net. The fish are soon spooked and descend out of sight to join the main body of fish, where they are also out of reach. Mr Smith might be able to photograph one of these fish, but he could never catch one. The difficulty for farm staff is weighing up the removal of a few fish against stressing thousands. Such choices are never considered in the negative coverage.

In his comment of February 10th, Mr Smith states that “every day, I research, listen and learn more about salmon farming and there’s plenty more for me to understand but I’m comfortable that my views are relatively informed and reasonable.” He also said that he would be happy to debate the issues as he did during the townhall tour around Scotland in 2019 (with the Patagonia film). However, he and Andrew Graham Stewart were less willing to do so at the premiere of the film in London where I was specifically asked not to pose any questions during the event on the understanding that Patagonia would arrange a separate meeting with me. This of course failed to materialise.

Mr Smith says he will be organising more of these townhall presentations once the pandemic is over so the discussion, debate and arguing can continue. The question is what does he want to talk about? We know fish, whether farmed or wild, defecate into the sea. We know salmon, whether farmed or wild get infested with sea lice. We know that salmon, whether farmed or in the wild eat small fish. The question, given Mr Smith’s angling background, is whether salmon farming has any impact on the environment? Whether it is responsible for the decline of wild salmon and sea trout? Whether the welfare of farmed salmon is compromised more than wild fish when they are dragged round by a hook in the mouth for the sport of anglers. However, I suspect that these are issues that Mr Smith is not so willing to discuss because he fundamentally knows that his attack on salmon farming is just a smokescreen for the wider problems of the wild fish sector.

Dyeing to paint: The Seaspiracy film returns to Mr Smith where he continues to demonstrate that his knowledge of salmon farming is severely lacking. He talks about salmon’s pink colour:

“Farmed salmon without colourant being added to the feed would be completely grey to the extent that salmon farmers can actually select from a colour chart much like you get when you are painting your house. You can select the pinkness of the salmon that you get to produce. So, it would not be for me to say, but it does seem like that people are eating grey fish that have been painted pink

He says that it would not be for him to say that people are eating painted salmon, but he still manages to do so. He equates the pink colour to the colour on a paint chart, but he would realise he is incorrect just by looking up the definition of paint – a coloured substance which is spread over a surface and dries to leave a thin decorative or protective coating. However, if Mr Smith were to cut through the flesh of a salmon, he would see that it is not a surface coating but is spread throughout the flesh.

Whilst Mr Smith refers to the pink colour as paint, the other critic in the film Don Staniford, like many others, often refers to salmon as being dyed pink. Dying is a chemical reaction that is usually irreversible and occurs when something, usually a textile, is soaked in a solution of chemical dyes. Hair can also be dyed, and this is because it is akin to a textile fibre. In cases, where dyes accidently are applied to the skin, it is not absorbed into the body but remains on the surface.

Mr Smith says that farmed salmon are naturally grey, but seemingly he fails to realise that the wild salmon he so covets, are also naturally grey. Of course, Mr Smith has probably only seen salmon flesh from fish that has returned from their feeding groups, which he has caught and killed for his sport and thus assumes that all salmon are pink. Returning salmon have grown fat by gorging on shrimp and other crustaceans which are naturally rich in a pink pigment called astaxanthin. The shrimp do not look pink when alive because the astaxanthin is chemically bound to a protein called crustacyanin, but when the shrimp is cooked, the protein is destroyed and the astaxanthin is released. This then turns the shrimp pink.

In the wild, when salmon eat the shrimp and other crustaceans, the protein is broken down during digestion and the astaxanthin freed to be absorbed by the salmon’s body and laid down in the flesh. Interestingly, other fish eat similar crustaceans but don’t lay down the pigment in the flesh. It is likely that evolutionary pressure of the salmon’s anadromous migratory behaviour.

Salmon produce fewer but much larger eggs than many other fish. These enable the fry to feed off a yolk sack that affords them more time before they must swim free and seek food. It also means that the fry are larger and have a better chance of survival through the early days. The larger eggs and longer development time require the extra protection of high carotenoid and antioxidant loads. These come from the pigment stored in the flesh during development of the ovaries. It is only when salmon have returned to freshwater to breed that the changes needed to produce eggs begin. Not only does the external appearance of the fish change but the ovaries grow, and the pigment migrates from the flesh into the eggs, which is why salmon eggs are bright red. If the pigment was painted or dyed in place as Mr Smith suggests, it would be permanent, but it isn’t. The movement of the pigment from the flesh to the eggs means that the flesh returns to its greyish colour.

Of course, farming means that the fish must be supplied with all the nutrients they require including antioxidants such as astaxanthin which is supplied in a natural identical format. Astaxanthin is not a paint or a dye but a nutrient, in fact it is a precursor to Vitamin A. Astaxanthin has between 100 – 500 times the antioxidant capacity or Vitamin E and prevents degradation of the fat cells which are crucial in protecting poikilothermic (cold blooded) species such as salmon.

If it is a paint as Mr Smith suggests, he might seek it at the local DIY warehouse but in fact, it is also available as a food supplement for human consumption due to its strong antioxidant properties and can be bought freely from health food shops.

Salmon are not the only animal to require carotenoids in their food. Laying hens also benefit from the addition of carotenoids to help with yolk development. The nutrition company also produce a colour fan for egg yolks, but I don’t hear Mr Smith suggesting egg yolks are painted, despite being exactly the same process.

Interestingly, whilst Mr Smith denigrates grey flesh salmon, some consumers value its appearance. In North America, some King (Chinook) salmon – about one in twenty – have white flesh due to a genetic determined inability to metabolise the pigment. For many years, these pale flesh coloured fish were considered of less value but more recently, the fish marketed as Ivory Kings bring a much higher price. Interestingly, salmon farming activist, Alexandra Morton recently wrote that during the late 1980s, she visited a salmon farm that was rearing Chinook salmon from eggs obtained from a public hatchery, and she was alerted to the fact that these fish were an abnormal colour – white. She wrote that no-one would tell her why the fish were that colour, implying that this was yet another dark secret of the salmon farming industry whereas the truth was that these hatchery-raised fish had a higher level of the genetic determined inability to metabolise pigments.

(Lusamerica)

(Lusamerica)Finally, the Guardian newspaper has recently highlighted that Tate Britain will be bringing back their Art Now Cooking Sections exhibition when the gallery reopens in May. The exhibition is titled Salmon: A red herring.

The exhibition explores the relationship between how we eat, and the climate emergency as perceived by Daniel Feranadez Pascual and Alon Schwabe. Unfortunately, the two ‘artists’ have been listening too much to people like Mr Smith because it focuses on the changing colours of species as warning signs of an environmental disaster. Their installation questions what colours we expect in the ‘natural’ environment as the planet changes as illustrated by salmon which must be fed synthetic pigments to make them the expected colour. They claim that humans and animals ingest synthetic substances and the subsequent changes in flesh, scales, feathers, skin, leaves (sic) or wings provide clues to environmental and metabolic changes around and inside us.

Unfortunately, the whole basis of the installation and its focus on salmon pink is misplaced. Salmon are naturally grey, not the result of environmental or climate changes but what is most sad about this complete failure to understand the natural changes during the salmon’s life, whether in the wild or farmed, is that prompted by the project, the Tate has decided to permanently remove salmon from its food outlets. All that can be said is that if they are so concerned about the inclusion of carotenoids in animal feeds, then maybe they should also act to remove all eggs and egg derived foods from all their outlets too.

Ahead of time: On his Facebook page, Mr Smith says his organisation – Inside Scottish Salmon Feedlots calls for the following:

- The Scottish Government to deliver a regulatory framework which will ensure an immediate and continued reduction of total emissions of sewage, chemicals, plastics, parasites, and disease by the open cage salmon farming industry

- The Scottish Government to commit to a closed containment and emission free salmon farming industry by 2030

- The Scottish Government to make transformational investments in communications, transport, and facilities throughout Scotland to ensure the nation can compete globally in the production of closed containment farmed salmon

One of the regular claims made against the Scottish salmon farming industry is that everywhere else besides Scotland is now moving to closed containment and Scotland is likely to get left behind, remaining dependent on out-of-date open water net pen production.

Of course, being a relative newcomer to salmon farming, Mr Smith is largely unaware of the development of the industry before 2015. If he did some proper research, he might know that thirty years ago, eleven sites were rearing salmon in shore-based tanks or raceways. This amounted to about 6% of production. None of these eleven sites are producing salmon now and for very good reason. They didn’t work out or were uneconomic.

Mr Smith claims that the Scottish salmon industry is blinkered to new development. I would suggest that the industry has tried the onshore option and found it to be somewhat wanting. The passage of time has not changed this.