Traffic stop: Fish Farming Expert reported that the salmon farmers challenging the Norwegian Government over a 6% reduction in biomass due to the Traffic Light system have lost their case. This was somewhat inevitable because the Norwegian Aquaculture Act permits the Government to vary production at their discretion.

The problem for the Norwegian salmon farming industry is not the way that the Traffic Light system is administered, but rather that the Traffic Light system is inherently flawed. It is this that needs to be challenged and not by just a group of farmers, but by the whole Norwegian salmon farming industry.

Ironically, for a system that depends on red, yellow and green lights, the warning lights have been shining brightly towards the salmon farming industry for quite some time. I just don’t think anyone was looking.

I shall be discussing various aspects of the Traffic Light system in future issues of reLAKSation.

Landed: All one hears from critics, whether it be anglers or those who claim to be environmentalists, is that land-based farming is the only solution. Certainly, the whole premise of the Discovery Island closure is that land-based farming is a viable solution to saving wild salmon stocks. According to the critics, land-based farming is practised the world over. What they mean is that land-based salmon farming is perceived amongst the financial sector as the latest way for investors to make money. In fact, land-based farming is very much investor-led and like many great investments before this, there are always people willing to persuade investors of the merits of the latest schemes.

This week news broke that the most well-known land-based salmon farming company, Atlantic Sapphire, suffered further losses of fish amounting to 500 tonnes at their Miami facility. According to Salmon Business, the company blamed a design weakness that allowed particles to escape from the filtration system. Atlantic Sapphire have pointed the finger at their RAS supplier. Of course, it is easy to blame someone else. However, the reality is that the Miami farm is Atlantic Sapphire’s second facility. They have a pilot farm in Denmark, which has experienced a number of different problems. Surely, Atlantic Sapphire should have enough experience of running RAS to know the pitfalls and to ensure the design is exactly right for their needs. However, this latest mortality suggests that they are far from having a viable working farm and if Atlantic Sapphire cannot get it right, what hope is there for all these new companies that have no experience at all?

Atlantic Sapphire’s share price fell by nearly 10% on the news, which should send a clear message to advocates and investors of land-based salmon farming. There is a reason why the salmon farming industry is not rushing to build land-based farms. It is not as easy as all those critics suggest. They are just selling one big lie for which investors will ultimately pay the price. It will be interesting to see whether this latest news has any impact on the €2 billion supposedly committed to land-based investments.

Philanthropy: It seems that in 2017, the organisation Open Philanthropy provided £805K of funding to Compassion in World Farming to support their work on fish welfare. In 2019. CIWF received another two grants totalling £1.7million, some of which was intended to bolster their work on fish farming.

This week, CIWF, together with One Kind, published their report Underwater cages, parasites and dead fish based on their undercover investigation supported by a global network of 30 organisations.

If Open Philanthropy get to read this report, I expect that they might ask for a breakdown of how their funding has been spent because one thing is abundantly clear, it hasn’t been spent on this report. It very much appears as if it has been written using the Google search engine without any real industry knowledge. Perhaps Open Philanthropy should ask for their money back?

Apparently CIWF have tweeted that they take their responsibility to ensure that their materials are factually accurate very seriously and have asked to hear from anyone who feels that their report is inaccurate and misleading. The question is where to start?

However, as I have mentioned previously, such organisations rarely rely on content to promote their cause but prefer to use one or two strategically placed images, usually taken out of context, to get their message across.

3,000: According to Fish Farmer magazine, Fisheries Management Scotland (FMS) believes that at least 3,000 farmed salmon may have found their way to Scottish and some northern English rivers after Storm Ellen struck the Carradale North salmon farm in August last year. However, what FMS believes may be completely different as to what actually happened. It is very much speculation on their part and unfortunately, their long-awaited report fails to answer many questions.

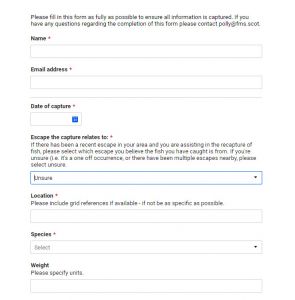

What we do know is that on 20th August 2020, a reported 48,834 salmon were inadvertently released from net pens which were damaged when the storm hit. We also know that by the 26th of August, FMS and the Ayrshire Fisheries Trust had issued a reporting form for anglers to complete and submit if they managed to catch one of these fish. The instructions were clear that the information required included details of the location where the fish was caught, its weight, as well as a photo and a scale sample.

Finally, on 31st August, FMS issued new advice on the capture of any farmed salmon. They say that if a fish is clearly of farmed origin the fish should be humanely despatched, even if caught from a category 3 river which has mandatory catch and release. They also say that the fish should not be consumed.

From September onwards, what we do know becomes increasingly hazy. Unfortunately, this new FMS report provides little clarity. The report is presented as if it is a scientific study, but it is a long way from being anything of the kind. It is simply a scale reading exercise by Ayrshire Fisheries Trust, verified by Marine Scotland Science but even on this simple exercise, the two organisations cannot agree on the number of salmon identified as of farmed origin.

In total, FMS and their associates received 466 reports of farmed salmon being caught from nearby rivers. This consisted of 310 complete records (details of catch plus photo plus a scale sample); 29 records of the catch details plus a photo but no scale sample and 127 records of details of the catch but without any photo or any scale sample.

FMS say that the reason why not all the records were complete was because some were not submitted through their reporting system. Yet, FMS also say that they worked closely with all relevant stakeholders including the Argyll Salmon Fishery Board, Argyll Fisheries Trust, Ayrshire Fisheries Trust, Clyde Foundation, Loch Lomond Fisheries Trust and Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association. FMS state clearly that ‘All were actively involved in developing a coordinated response and subsequent monitoring of the escape.’

Given this coordinated response, it is inconceivable that any proprietor was not aware of the reporting system nor the need to pass on that information to anyone fishing their waters. As the instruction was that the fish had to be despatched, there can be no excuse that the fish was not available either to photograph or to remove a scale sample. This is a vastly different scenario to an angler trying to return a caught salmon back to the river with minimal handling or fuss. In my opinion, there is only one reason why scale samples of caught and despatched fish were not supplied, and this is because this event provided anglers with a ready excuse to kill the fish they caught for the pot, irrespective of its origin. In all 33% of the records were incomplete suggesting that over 156 wild salmon were despatched yet claimed as farmed.

In addition, another 15 fish for which scales were submitted proved to be wild fish and were killed regardless.

In total, FMS list 23 rivers where farmed salmon were allegedly caught but six of these produced no verified records of capture so can be discounted. Anglers from four Scottish rivers were responsible for the most unconfirmed captures (92%). These are:

Doon – 14

Echaig – 31

Girvan – 23

Leven – 76

One English river also produced 11 unconfirmed captures. This is the Derwent, which had just one confirmed fish.

By comparison, the River Stinchar had 51 confirmed captures and only one unconfirmed. It appears that anglers on this river were most effective at complying with the request to report the appearance of farmed fish.

In all, 295 salmon were identified as farmed by scale reading or 277 as confirmed by Marine Scotland Science. This equates to 0.6% of the fish released by the storm. This compares to 0.1% salmon of farmed origin caught against the total salmon catch across all of Scotland for 2018. It is likely most of the fish swam out to sea never to be seen again. Yet, FMS estimate that about 3,000 fish or 6% of the released fish have entered these rivers.

FMS base this estimate on the general acceptance that anglers catch about 10% of the wild salmon entering Scotland’s rivers. They therefore say that the same must apply to these farmed salmon. This is absolute nonsense. This is because wild salmon return to Scotland’s rivers throughout the year and spread out throughout the river’s length. In addition, anglers can fish for nearly ten months of the year and fishing pressure has generally, until recent years, been relatively stable.

This event has happened over a short period of time and there is no evidence that these fish have spread out throughout the length of these rivers. Even FMS admit that the fishing pressure is uneven with many more anglers active on the River Leven, probably due to its proximity to Glasgow. FMS also state that they think that their claim of 3,000 fish is an underestimate but of course, they want to portray this event in the worst possible light.

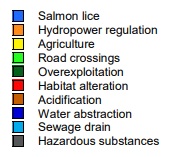

FMS provide two indicators of the spread of those fish confirmed as of farmed origin. The first is a map of all the rivers from which these fish were caught, stretching from the Echaig in the north to the Lune in the south. The Lune empties into the sea at Lancaster, which is about 250 km south of the farm. FMS say that all the captured fish were of a similar size to those from the farm, but this distance might be a bit extreme, especially in such a relatively short time.

FMS also provide a graph showing the number of fish caught each day. I have consolidated this data into weekly catches showing that most salmon were caught mid to late September.

What FMS do not show is the geographic location of catches on a week-by-week basis so that the spread of the salmon can be observed. Equally, FMS have failed to show the exact location on each river from which the salmon were caught. I have written previously that I had heard reports that the fish appeared in the lower reaches of some rivers for just a couple of days and then were never seen in the river again. Plotting the location of every capture would have identified the extent to which these salmon had penetrated into the river.

FMS suggest in their report that these fish when they enter the river have the potential to do substantial damage to the wild population. Although these specific fish were not sexually mature, the potential to interact is minimal if the fish do not remain in the river. Thus, it is important to understand how far up each river the fish were caught. As anglers supposedly provided information as to the beat being fished, such an investigation is perfectly feasible, yet it is one that FMS has failed to conduct.

FMS particularly highlight the catches from the River Leven, part of the Loch Lomond system. They focus on this system because one of the rivers feeding into Loch Lomond is the River Endrick (or Endrick Water). FMS state that:

‘The River Endrick is designated as a SAC with Atlantic salmon species present as a qualifying feature. Site condition monitoring undertaken by NatureScot shows this Special Area of Conservation is currently in an unfavourable condition.’

FMS don’t actually draw any conclusion from this statement in their report but clearly the implication is that the presence of farmed fish is a threat to the SAC. However, the inclusion of this short reference to the Endrick SAC brings into question the accuracy and validity of the whole report. Both statements about the Endrick SAC are not only incorrect but so is the overall assumption.

Endrick Water was selected as an SAC because of its general character. This is due to it being an inland water body making up 92.5% of its area. The other characteristics are the 3% bogs, marsh and water fringed vegetation mixed with 3% arable land and 2% broad leaved deciduous woodland. If you are wondering what this has to do with salmon, then the answer is very little. SAC’s are part of the Habitats Directive and the clue is in the name. It is the habitat that is protected not the species. In the case of Endrick SAC, the characteristics are an ideal example of habitat for both Brook and River Lampreys. Salmon are listed because they are a qualifying feature as FMS state but not as the primary reason for selecting the area as an SAC. Thus, if lampreys were not present, Endrick Water would not be a SAC. There are other SAC’s that have been selected because they are good examples of salmon habitat, but the Endrick Water is not one of them.

The second inaccuracy is that the Endrick Water SAC has been assessed as being in an unfavourable condition. In fact, NatureScot have classified the river as ‘Unfavourable Recovering’ which is not the same at all. Interestingly, NatureScot highlight fisheries management as one of the negative pressures leading to the rivers’ current classification. Perhaps, FMS should be more concerned about the way the fishery is managed by its members rather than the presence of a few salmon of farmed origin.

Other rivers that have been selected as an SAC and do appear in FMS’s list of locations where confirmed farmed salmon have been caught, include the River Eden and the River Derwent, both in Cumbria. Another river that has been selected as an SAC for salmon is the Bladnoch which is located on the Solway Coast near other rivers that have reported confirmed farmed salmon, yet anglers fishing the Bladnoch appears to have failed to catch any salmon of farmed origin because it is not included in FMS’s list. The River Ehen in Cumbria is another SAC, but like the Endrick has not been selected because of its salmon. Two salmon of farmed origin were caught from this river.

FMS are not alone in highlighting what they consider potential damage to SACs, Salmon & Trout Conservation have notified NatureScot and the Environment Agency that they expect the SAC’s to be under threat due to the presence of the farmed salmon released from this farm and that these agencies should take remedial action. S&TC highlight the Endrick, the Eden and the Derwent but omit to mention the Bladnoch and the Ehen.

However, the fundamental issue that both FMS and S&TC choose to ignore is that the presence of salmon of farmed origin makes no difference to the status of the SAC. It is the habitat not the fish that is being assessed. FMS and S&TC might disagree, but this is easily demonstrated. The River Tay SAC was designated in March 2005. Since that date, 39,200 salmon and grilse have been caught and killed from this Special Area of Conservation. Given what FMS and S&TC suggest, then why are these fish being killed in this protected area? The answer is that it is not the fish that are protected but the habitat. The presence, or not, of salmon of farmed origin is totally irrelevant.

Both FMS and S&TC also omit to mention another SAC on Scotland’s west coast. This is the Little Gruinard river which is not far from Ullapool. FMS appears to have focussed their efforts to the south of the release area but the prevailing currents head north. It is possible that fish from the farm could have headed north, just as easily as they swam south, yet there are no reports of fish recaptured in this area. Is this because, the question wasn’t asked or that no-one was interested?

Finally, the introduction to this report states that ‘for populations of wild salmon already below their conservation limits even a small number of farmed salmon interbreeding with wild salmon can have a significant impact.’ This continues that ‘In Norway pressures from salmon farming are considered to be the greatest threat to wild salmon.’ This is linked to a paper which makes no reference to interbreeding.

In the summary, FMS state that ‘the impact of genetic introgression is accepted within peer reviewed scientific literature.’ However, FMS make no attempt to justify this claim by citing relevant documentation. Instead, there is a reference to a single paper, yet one of the authors also authored a study in which salmon of farmed origin found in Norwegian rivers were genotypically more similar to wild salmon than can be attributed to coincidence.

Claims made by FMS about the negative impacts of salmon of farmed origin are likely to be related more to angling sector preconceptions than