Changing Markets: One of the environmental correspondents at the Guardian wrote about the new report from Changing Markets Foundation under the headline ‘Global salmon farming harming marine life and costing billions in damage’. In my opinion, it’s likely that this correspondent did not actually read the full report but relied on the press release and other news reports as the basis of her article. This would not be surprising as quite a number of the references used by Changing Markets Foundation come from other articles reporting headline news rather than looking at the issues in depth. More references come from other NGOs, charities and commissioned reports rather than original research.

In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if many others commenting on the findings of this ‘research’ had not bothered to read the report too. Reading it is hard work because it is factually incorrect, riddled with schoolboy errors and assumptions.

Changing Markets Foundation commissioned the report ‘Dead Loss’ from ‘Just Economics’ (JE) who work on research and policy but clearly don’t know very much about salmon and salmon farming. For example, they state on page 60 that ‘Canada is home to seven different species of Pacific salmon as well as Atlantic salmon on its eastern seaboard.’

Canada is actually home to just five Pacific salmon species, not seven. For those who don’t know the various species, a quick search on Google produces the following result:

Sorry, we haven’t a clue

However, what is of much more interest in this report, is the impact of salmon farming on wild salmon. Unfortunately, there is not a single separate section that looks at this issue. Instead, paragraphs are scattered throughout, which makes it harder to make sense of an already difficult subject. I hope the following covers all aspects of the report with regard to wild salmon.

Findings

In the section titled ‘Findings’ JE begin by referencing the work of Thorstad and Finstad from Nina in Norway. They say that ‘a recent study found that ‘the presence of a salmon farm can lead to an average of 12-29% fewer adult salmon in the local area’. Actually, Thorstad and Finstad didn’t say that at all. What they said was that experimental studies of lice induced mortality in salmon smolts from between 2011 and 2014 found that 12-29% fewer unprotected than protected fish were recaptured as adults. It is also worth considering that Thorstad and Finstad were commissioned by Salmon & Trout Conservation Scotland to produce their report as proof salmon farming has a negative impact on wild salmon and thus in my opinion the report is written to reflect this commission. How the mortality is expressed has been a long running issue amongst the scientific community. Dave Jackson, in his 2013 paper found mortality of sea lice was about 1%. Critics suggested that if two protected fish returned and only one unprotected then the difference was not 1% but rather 50%. They compare the number of fish that have returned to each other rather than comparing the number of fish returning to how many were originally released. The numbers are the same, but the problems occur when the 50% is applied to a salmon population rather than just 1%.

I raise this because JE move on to say that their estimate of 20% mortality due to salmon farming is close to the midpoint of the estimates of 12-29% provided by the Thorstad and Finstad (2018) study.

Twenty percent mortality

What is now interesting is to look at how JE arrived at a figure of 20% mortality.

They begin by saying that their full methodology for each country is set out in the national appendices but in this ‘Findings’ section they summarise that one study has found that salmon farms kill 50,000 wild salmon in Norway per year. This information comes from a New York Times report which in turn links to the 2017 annual report by Vitenskapsradet.no (VRL) even though the 2020 annual report is already available. The figure of 50,000 comes from VRL estimates from 2010 to 2014. Later figures show 28,000 for 2018 and 39,000 for 2019. Of course, as I have regularly pointed out, these figures are all estimates calculated from mathematical models and VRL are unable to provide evidence that such numbers of fish actually died as a result of salmon farming.

JE continue that if it is assumed that a similar number of salmon are killed due to infectious disease then a total of 100,000 fish (50,000 plus 50,000) are at risk from salmon farms.

Significantly, they then say that ‘we have excluded the impacts of escaped salmon as the impacts are not well understood’. I’ll return to this point.

They continue that we also know that there are half a million fewer salmon returning to Norwegian rivers each year than there were in the 1980s. The latest VRL report puts the number at 481,000 which is actually higher than the 470,000 in 2016 but lower than 543,000 in 2018.

However, JE have taken the headline figure that numbers of returning salmon have halved from one million fish in the 1980s and thus assume a figure now of half a million of which a 20% loss would be 100,000 fish broken down into a loss of 50,000 due to sea lice and 50,000 due to infectious disease. As already discussed, they suggest that 20% figure is about mid-way of the estimates provided by Thorstad and Finstad of 12-29% for mortality due to sea lice. Yet as only 50,000 deaths are due to sea lice, their figure should be 10% of returning salmon and not 20%. Of course, this ultimately depends on whether the figures estimated by VRL’s model are accepted as a realistic mortality.

Between 2010, and 2014, the number of salmon returning to Norwegian rivers was about 500,000 fish so VRL’s estimate of 50,000 fish equates to less than the numbers offered by Thorstad and Finstad in 2018. Eve Thorstad is one of the two leaders of VRL so depending on which of her reports is read, the numbers appear to conflict. Dave Jackson from the Marine Institute in Ireland found through practical experiment that the mortality due to sea lice was about 1% which makes the Norwegian mortality due to sea lice at 5,000 fish and since there are rivers in Norway without salmon farming, the number is probably even less. For comparison, 136,000 salmon were killed by fishermen and anglers in 2019.

JE also attribute the deaths of 50,000 salmon to infectious disease from salmon farming. They do not say how they arrive at this figure. VRL place such infections high on their graph of risks to wild salmon but they say in their latest annual report:

“Infections related to fish farming were also identified as a threat that can significantly impact salmon, and with a large likelihood of causing further reductions and losses in the future. However, knowledge of the impacts of infections related to fish farming is poor, and the uncertainty of the projected development of this impact factor is high. More knowledge on this impact factor is needed. There is a risk that this threat is underestimated due to lack of knowledge.”

In a nutshell, they haven’t a clue.

However, in Scotland, the reasons for farmed salmon mortality are listed for every event by the Fish Health Directorate and there is very little evidence of infectious disease. There is even less evidence that should an infectious disease occur it will be transferred to wild fish. At present, JE cannot attribute 50,000 potential deaths of wild salmon in Norway unless they have evidence that has not yet been published.

Norway

All the above comments relate to the content of the section headlined ‘Findings’. There are also four appendices relating to each of the countries investigated. Appendix 1 concerns Norway. It is simplest if I copy their comments directly from the report:

“Impacts on escaped salmon are difficult to model but it is estimated that lice from salmon farms kill 50,000 wild salmon per year. We know that returning salmon are about half a million fewer than in the 1980s. If we conservatively assume about 150,000 of these are as a result of salmon farming (we know 50,000 are due to lice infestations, and assume 75,000 are due to hybridisation and 25,000 due to infectious diseases). This is about 30% of the lost wild salmon population.”

So, within seventeen pages, it seems that JE forgot what they had identified as the threat to wild salmon in Norway. Instead of 50,000 deaths from infectious disease, JE now say that only 25,000 wild fish will die after picking up a disease from farmed salmon. However, more interestingly, having said that they have excluded the impacts of escaped salmon as the impacts are not well understood, they have now managed to assume that there will be 75,000 fewer wild salmon due to hybridisation from escaped salmon. VRL discuss escaped salmon in their annual report but do not offer any specific impact in terms of numbers. Not unexpectedly, they just say that escaped salmon are a threat to wild salmon.

Sums that don’t add up.

In reLAKSation no 1004, I discussed a study from FHF that found only a small number of fish that are genetically identified as coming from escaped farmed stock find their way up the rivers and successfully spawn, but crucially, that these fish have a greater similarity to wild salmon than they have to the various breeding stocks from which they originate. The conclusion was that natural selection is weeding out the salmon that are not adapted to life in the wild. By comparison, those salmon with the best adaption to life in the wild are the ones that survive. Unfortunately, VRL appear to ignore this study as it doesn’t support their narrative.

The final point about Norway is that JE have now stated that salmon farming is responsible for 30% of the mortality of wild fish, up from 20% expressed in the findings section.

Scotland

Appendix 2 concerns Scotland. JE state that (wild) salmon stocks have seen dramatic declines, halving in 20 years to 2016 to just over a quarter a million. “As with our Norway estimates, if we assume that 20% of these are due to salmon farming, we arrive at an estimate of 71,000 wild salmon being lost to fish farming each year.”

If wild salmon stocks have halved to just over a quarter of a million fish in twenty years, logic would say that the stock has been reduced by 250,000 fish, 20% of this number is 50,000 fish not 71,000. Using their other figure of 30% equates to a greater number of 75,000.

71,000 fish actually equate to a figure of 28.4%. Finally, if 71,000 is 20%, then the stock size would be 355,000 fish not 250,000.

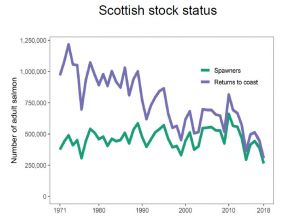

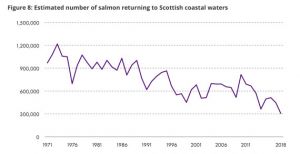

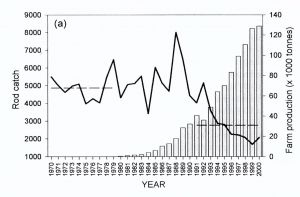

This graph comes from the head of the Freshwater Fisheries Laboratory at Pitlochry and was used in a presentation this last week. It is therefore the best information available. It shows stocks have been declining for longer than the last 20 years and at a time when salmon farming was still in its infancy. It is worth pointing out that the difference between the number of returning salmon and those spawning are fish that have been killed by netsmen and anglers.

According to the graph and a similar one produced for the Scottish Parliament by SPICe, the number of returning salmon is about 300,000 fish. We also know from catch data that the salmon stock on the west coast is currently about 30,000 fish. Unlike Norway, Scotland has different coastlines and salmon farming is limited to just one of them. If the mortality was 20% as JE claims, then the number of wild salmon would be reduced by 6,000 fish and not 71,000. Using Jackson’s work and a mortality of just 1% due to sea lice, then the salmon farming would be responsible for the return of just 300 wild salmon. For comparison, anglers caught and killed 3,786 wild salmon in 2019 for sport across all of Scotland.

Canada

Finally, I would like to turn to Canada (Appendix 3). JE report that according to NASCO, Atlantic salmon numbers have declined by 41% since the 1980s. This equates to 627,415 fish with just 436,000 salmon returning to Canadian rivers. JE assume a 20% loss due to salmon farming (they say to see Norwegian assumptions which actually state 30%). They thus calculate that salmon farming is responsible for a loss of 188,244 fish.

What is interesting is that they fail to include the loss of any Pacific species from the BC coast. This is the source of most of the claims that salmon farming is responsible for the declines of wild salmon, but JE ignore this whole coast.

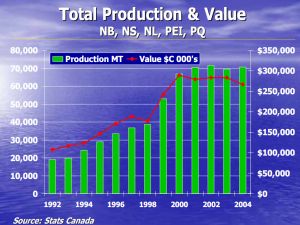

The following graph is the production of Atlantic salmon in Eastern Canada, which is where stocks of wild Atlantic salmon can be found.

This graph is a bit out of date, but production has remained relatively similar in the years since at below 60,000 tonnes. This means that according to JE, 60,000 tonnes of salmon production in Eastern Canada is responsible for a decline of 188,244 wild fish. In Scotland, salmon production of around 200,000 tonnes is responsible for 71,000 fewer salmon returning to Scottish rivers and in Norway, production of over 1.3 million tonnes has resulted in 150,000 fewer salmon. What is interesting is that whilst JE use 20% (or 30%) mortality across the three different nations, the ratio of tonnage produced to mortality is so widely different between them.

It seems that in the case of this report, the sums simply don’t add up.

No comment

I want to finish by saying that this is my analysis of the Changing Markets report. I would have been interested to hear a response to the points I have raised. I therefore wrote to ‘Just Economics’ copied to Changing Markets PR company.

Their reply took the form of attacking the messenger rather than addressing the message. They said that they wouldn’t answer my questions as I would no doubt distort the facts and findings of their report.

They also said that Changing Markets are being continually ‘trolled’ by Twitter account @TalkSalmon which they believe belongs to me. I don’t know how many times I have to repeat myself, but I don’t need to hide behind any anonymous account. I am more than happy to stand up and voice my opinions under my own name.

The anti-salmon farming critics cannot believe that there is more than one person willing to stand up and defend inaccuracies levelled at the salmon farming industry. I don’t know when I would have the time to manage and respond to all the social media accounts that are supposed to be run by me.

Finally, it is a puzzle how an NGO thinks that they can put out an inaccurate report attacking an industry and not expect there to be a response. What is an even greater puzzle is that they are then so reluctant to defend their report?

Norwegian Experts: According to Kyst.no, Peder Jansen, a former member of the Traffic Light Expert Group and now a senior advisor at Inaq, gave evidence in court at the case of the farmers from the PO4 area who fighting the government’s decision to switch the red light on in the PO4 area.

Jansen told the court that he was surprised that there was such a poor match between the model’s predictions and the actual observations made in the area. Yet, I am not sure why he should be so surprised. Why would a model built by academics be expected to be an accurate reflection of what happens in the natural world? Any model, however good, relies on the preconceptions and views of those who build it and unfortunately, there is a small network of academics who believe that salmon farming is detrimental to wild fish. As I have mentioned in a previous reLAKSation, their views are based on the simple correlation between declining wild fish stocks and growth of farmed salmon production. Corelation doesn’t prove causation but they have fixated on salmon farming ever since. The current leader of the expert group, Knut Vollset from NORCE was asked whether mortality from lice correlated with general conditions and whether this was something they had considered. Professor Vollset replied that they cannot prove why there is a connection with lice, but they see that it is the case.

I find it interesting that Professor Vollset’s Twitter feed leads with a pinned Tweet about a paper he was the lead author which considers sea lice, salmon and the Traffic Light system. The salmon industry in Norway doesn’t stand a chance when the expert group consists of experts with such fixed views on lice. In my opinion, it hasn’t helped that salmon farming has become a cash cow for Norwegian academic research so why would anyone engage in research that would absolve salmon farming of any blame. This paper was funded by the Norwegian Research Council. The paper is co-authored by others who are connected to or have been connected to the expert group but of more concern to all Norwegian salmon farmers, the paper is also co-authored by two directors of the Salmon Coast Field Station, the facility established by anti-salmon farming critic Alexandra Morton. It was her ‘science’ that has led to the forthcoming closure of 19 salmon farms around the Discovery Islands in Canada as well as others in the Broughton Archipelago. Could such close cooperation with members of the expert group lead to salmon farm closures in Norway? Anything is possible.

Summary of the Science: In a previous issue of reLAKSation, I discussed two of the papers which supposedly indicate that sea lice from salmon farms have a detrimental impact on wild salmon that are cited in the summary of the science provided by Marine Scotland Science on the Scottish Government website.

The unnamed authors of this summary then highlight a paper by Butler and Watt (2003). At the time, both authors worked for either one of the Fishery Boards or Fishery Trusts. James Butler went on to co-author the paper with Andy Walker about the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery.

This paper states that ‘The expansion of the (salmon farming) industry has coincided with marked declines in rod catches of wild salmon in the North West and West Coast Statistical Regions which cover the bulk of the salmon farming zone. Over the same period, rod catches outside the salmon farming zone in eastern and northern Scotland have increased by 30%. This trend raises concerns that salmon farming is impacting upon wild salmonid populations.

Ignoring the fact that Middlemas, Smith and Armstrong have written in a Marine Scotland Science report (2016) that “Broad scale comparisons of catch data (East/West, farming/non‐farming) is not ideally suited to providing evidence of any impact of fish farming” the fact that the same report shows that catches did not continue to decline as production continued to grow.

Whilst catches did not recover to past levels, catches on the east coast also fell into decline, reflecting greater problems across all of Scotland.

The Butler and Watt paper does not prove any link between salmon farming and wild fish declines and should like the other papers I have discussed, be removed from this summary of the science. If Marine Scotland Science would like to justify why these papers are referenced in the summary of the science, I would willingly share their response in a future issue of reLAKSation.

I will continue to explore other referenced papers in future mailings.